This article was originally published on ABC’s The Drum. Read the original article here.

Although Joko Widodo (popularly known as Jokowi) still appears likely to become Indonesia's next president, yesterday's election result may make it more difficult for him to push through an agenda as president.

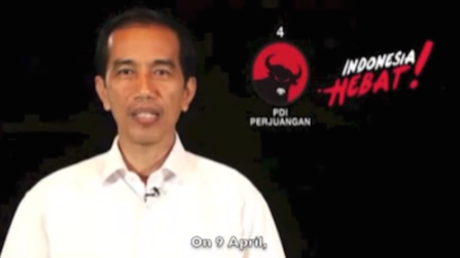

Much of PDI-P's election campaign employed the premise that a vote for PDI-P was a vote for Jokowi as president, and Jokowi repeatedly called for voters to deliver a wide margin to PDI-P to give him a strong parliamentary base. He now faces the same prospect as his democratic-era predecessors, of governing with a minority of seats under his own party's control.

All of Indonesia's democratic-era presidents addressed this challenge by forming so-called "rainbow coalitions", involving most large parties in the national legislature. This strategy has not proved to be an effective way to lock in support for a coherent government agenda. When Yudhoyono formed a rainbow cabinet in his second term despite a landslide presidential election win, coalition partners began to criticise elements of the government agenda from very early in his term.

PDI-P chose to remain outside the cabinet for both of Yudhoyono's terms, in part owing to enmity between the party's chairperson, former president Megawati Sukarnoputri, and her cabinet minister-cum-president Yudhoyono. Ahead of the election it had expressed the ambition to form a narrow coalition, but may now be tempted to form a much broader grouping.

Nevertheless, the arguments for keeping to a more limited coalition remain sound. One of Jokowi's main assets as president will be his ability to marshal public opinion in support of his agenda. A more promising approach remains to form a capable cabinet and have the president lend his personal political weight to key elements of his agenda.

It is worth underlining that a legislative campaign that often felt like a trial run for the presidential election has brought us no closer to knowing what Jokowi's precise policy agenda will be. Detailed policy discussion was generally absent from the campaign, which instead focused on the personalities of the main parties' presidential contenders. Jokowi is seen as an honest politician who meets directly with the common man and works to solve their problems, whereas Prabowo's signature quality with voters is his perceived firm leadership as a former military general.

At a campaign rally I attended in East Java, Jokowi said nothing about his policies and instead relied on attendees' affinity for him to ask them to work hard for an election result that would make him a strong president. As a small-town mayor and now Jakarta governor for the past 18 months, he has focussed on programs to extend health and education coverage, as well as bureaucratic reform and the consultative relocation of street vendors.

A president faces a much wider range of domestic and international policy questions, but Jokowi avoided comment on these issues prior to his confirmation. Although he has been the frontrunner in opinion polls for at least a year, he could not be seen to assume to be entitled to be PDI-P's candidate before party chairperson Megawati confirmed this fact. His virtual silence on policy has also kept Jokowi as a small target, and allowed those disillusioned with politics to project their hopes for reform on to him.

His opponents may now try to draw him out on these issues, in a bid to highlight his national-level inexperience. It is far from clear though that this will be a successful strategy. Ability to lead ranked well below honesty/trustworthiness and attention to the people in a recent survey of the most important qualities for a president.

Despite PDI-P's lesser than expected election result, Jokowi's considerable personal aura still looks set to carry him to be the next president.

Dave McRae is a senior research fellow at the Asia Institute at the University of Melbourne, and an associate at the Centre for Indonesian Law, Islam and Society. View his full profile here.