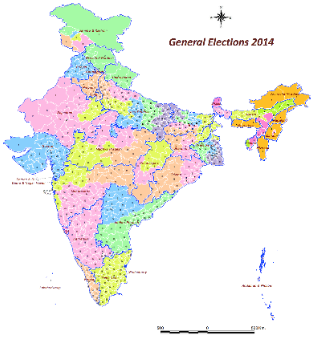

Almost like a boxing bout that's gone on just too long and left the fighters spent and worn, India’s 16th general election is now entering the final round. Voting for the final 41 seats in the Lok Sabha (Lower House) of 543 seats is taking place today.

Eighteen of these constituencies are in eastern Uttar Pradesh, a massive state that straddles India’s north and east. Seventeen constituencies are in West Bengal and six in Bihar, both in the eastern region of the country.

What is remarkable about this phase of the election is that the party that has led the government for the past 10 years, the Congress, is scarcely in contention. It matters in only a handful of seats.

In Uttar Pradesh, the battle is between the BJP and the Samajwadi Party (SP) and in some areas the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), both of which are robust state-level parties. In Bihar, the BJP is facing a challenge from the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), led by Laloo Yadav, one of India’s most charismatic and controversial politicians. Yadav has been convicted for corruption and debarred from contesting. His party’s formal challenge in this election is led by his wife and daughter.

In West Bengal, the Trinamool Congress, another regional party that runs the state government, is the front-runner. The Left Front, a conglomeration of four left-wing/Marxist parties, is expected to finish second but the BJP is hoping to win enough votes to record its best ever performance in a state where it has rarely got traction.

Two very senior politicians — both potential prime ministers — are seeking parliamentary election in this round. Mulayam Singh Yadav is a former chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, a former defence minister of India and the founder-leader of the Samajwadi Party. He is a candidate from Azamgarh.

Should a horribly hung Lok Sabha result when the votes are counted and a “Third Front” — or a post-election coalition of state and regional parties — take office, Mulayam Singh Yadav (left) could well be its prime minister.

However, Azamgarh may deliver a shock. Political assessments suggest Mulayam Singh Yadav is not quite well placed against his BJP rival.

The other big contest, and the one that has drawn the Indian and international media in the past few days, is in Varanasi, where BJP Prime Ministerial candidate Narendra Modi is the favourite.

Taking him on are Ajay Rai of the Congress and Arvind Kejriwal of the start-up Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), which was born in 2013 as an anti-corruption party but has expanded — some would say diverted — its energies into becoming a primarily left-of-centre, anti-BJP party.

Varanasi is one of the most iconic symbols of India and its civilisation. Reputed to the world’s oldest continuously-inhabited city it finds mention even in the Rig Veda, among Hinduism’s most ancient texts.

As a centre of religion and scholarship, and more recently textiles and tourism, and as a city defined by its relationship with the river Ganga, Varanasi (or Banaras) is in many senses central to Indian identity.

Politically, Varanasi is the informal capital of some 30-35 parliamentary constituencies stretching from eastern Uttar Pradesh into neighbouring Bihar. That is why Modi, who comes from Gujarat in western India, chose it, seeking to establish his presence in a political geography that the BJP felt could yield rich gains.

Opinion polls and political feedback — insofar as these are reliable — indicate this gamble may have worked. Of the 18 seats in eastern Uttar Pradesh that vote on May 12, the BJP is predicted to win about a dozen.

In Varanasi itself, despite Kejriwal’s energetic and media-friendly campaign, few doubt Modi will win. The race is for a strong second-place finish. (In essence, can Modi’s challangers — Kejriwal and Rai, a city strongman with a rough-and-ready reputation — capture enough of the vote to deny Modi a satisfingly big victory.)