Flinders Street station, after a tough day at work.

Your feet hurt, you’re hot and tired. As you take the escalator down to Platform 13 it’s plain that something is wrong. The platform is packed, more packed than it should be, and a glance up at the information board delivers unwelcome news. There’s no train for – how long? The screen’s blank.

Thirty minutes later a train finally leaves and you travel home with your face in an unwashed armpit. As you descend the ramp from the station, a tram pulls away in front of you, and you set off on foot for the fifteen-minute trudge to your front door. Finally, more than an hour after your journey began, you’re home, just 10 kilometres from the CBD. You collapse into a chair and switch on the TV.

Promised independent scrutiny hasn’t been delivered and the present government has followed the lead of its predecessor in continuing to blur the lines between genuine government communication and campaign advertising.

And there’s this advertisement on the screen. Relaxed, happy people enjoying a clean, fast, and connected transport system. Bearing no relation to your journey home. Who are they kidding?

And there’s this advertisement on the screen. Relaxed, happy people enjoying a clean, fast, and connected transport system. Bearing no relation to your journey home. Who are they kidding?

There’s an old adage in the advertising industry that the consumer won’t buy a dud product twice. This can’t be applied to political advertising. What choice do we have? One party promises to fix public transport and doesn’t, so you vote for the other lot and they don’t do it either. No wonder we’re such a cynical lot.

And there’s a lot to be cynical about when it comes to taxpayer-funded advertising in this state. Criticising the Brumby government for excessive spending on advertising (particularly its ‘Shine’ education ads – and more here) and the ‘Victorian Transport Plan’ campaign, the Coalition promised in 2010 that, once in office, it would cut back on advertising and set up an independent body to ensure future government advertising didn’t become too political1. But this independent scrutiny hasn’t been delivered and the present government has followed the lead of its predecessor in continuing to blur the lines between genuine government communication and campaign advertising.

And there’s a lot to be cynical about when it comes to taxpayer-funded advertising in this state. Criticising the Brumby government for excessive spending on advertising (particularly its ‘Shine’ education ads – and more here) and the ‘Victorian Transport Plan’ campaign, the Coalition promised in 2010 that, once in office, it would cut back on advertising and set up an independent body to ensure future government advertising didn’t become too political1. But this independent scrutiny hasn’t been delivered and the present government has followed the lead of its predecessor in continuing to blur the lines between genuine government communication and campaign advertising.

As the University of Melbourne’s Associate Professor Sally Young has shown, this convergence, especially in the build-up to an election, is a well-documented phenomenon at federal and state levels of government in Australia.

The Coalition’s advertising strategy can be unpacked from the Premier's website. The gameplan is plain: spruik the government’s achievements in improving transport infrastructure and public safety. Keep quiet (or quieter) about everything else.

We can tell this is so because transport infrastructure and public safety have been given their own slogans: 'Moving more people more often' (remarkably similar to the government's ‘Moving Victoria’ campaign slogan) and ‘Building a Safer Victoria’. Education and health don’t, as yet, have individual slogans; rather they sit under the broader slogan ‘Building a Better Victoria’, or, in the case of its campaign against the drug ice – which, despite the headline ‘What are you doing on ice?’ is aimed not at ice users but at the general public, to alleviate their fears and reassure them that the Coalition is acting to keep them safe – the government has hedged its bets, placing what is ostensibly a health campaign under the ‘Safer Victoria’ strategy.

Most of the advertising budget has been spent on communicating the Coalition’s achievements in transport infrastructure. The Premier’s website tells voters that in the 2014-15 budget ‘The Victorian Coalition Government announced the largest ever investment in transport infrastructure in Victoria's history’. Since its election, the government has provided 'more than 1,070 extra train trips a week' (although by my personal observation, clearly none of them on the Sandringham line).

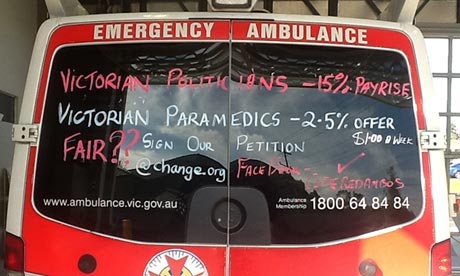

Contrast this with a campaign that has cost the taxpayer little or nothing. For the past few years, the paramedics have waged their campaign for better pay and conditions by airing their grievances on the windows of our ambulances. The government calls it ‘scurrilous graffiti’ but in advertising parlance it’s "ambient media" or "guerrilla marketing".

Contrast this with a campaign that has cost the taxpayer little or nothing. For the past few years, the paramedics have waged their campaign for better pay and conditions by airing their grievances on the windows of our ambulances. The government calls it ‘scurrilous graffiti’ but in advertising parlance it’s "ambient media" or "guerrilla marketing".

Ambient media packs a greater punch than a slick television campaign because it reaches people in less expected places; it takes them by surprise. In the case of the paramedics’ campaign that unexpected place is highly visible and serves to reinforce the message they wish to convey. The ambulance is hurtling along the highway to save another Victorian, slowing only to negotiate the traffic. The use of our ambulances in this way has divided Victorians, but overall the campaign has been targeted, effective, and on a platform money can’t buy. The government can’t come close to competing with it.

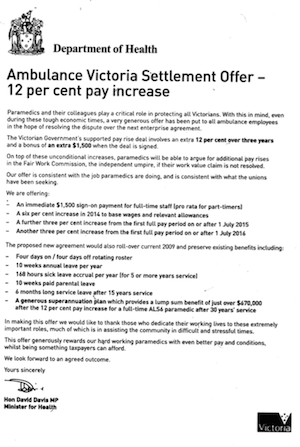

That point was underlined by the publication late last year of an extraordinary public letter from the Government to the paramedics (right - from The Age).

That point was underlined by the publication late last year of an extraordinary public letter from the Government to the paramedics (right - from The Age).

As with the ice campaign, the target audience for this letter, which appeared in Melbourne’s major newspapers, was not as it first appeared.

Signed by the Minister of Health, David Davis, and arguing that the government’s offer to paramedics was "very generous" in "tough economic times", the letter was aimed not at the paramedics but at the voters, in a bid to shift their sympathies in the dispute from the paramedics to the government.

Equally extraordinary were subsequent attacks on the government for wasting taxpayers’ money on selling itself from the very newspapers in which this advertisement appeared (find links in The Age here and here, and in the Herald Sun here). Which begs a question ... if the papers felt so strongly about this waste, why didn’t they refuse to run the ads? Oh yes … of course … But then the entanglement of the mainstream media in this frenzy of taxpayer-funded political advertising masquerading as government advertising is a discussion for another day.

ADDITIONAL REFERENCES:

1. ‘Brumby $100m ads splurge in election lead-up’, The Age, 1 August 2011; ‘Baillieu breaks promise on ad watchdog, The Age, 2 September 2012; ‘Victorian Government defends $314 million spent on advertising’, The Age, 19 January 2014.

Jackie Dickenson is a researcher based at the School of Historical and Philosophical Studies at the University of Melbourne. She is the author of Trust Me: Australians and their Politicians (New South press, 2013).