As former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg recently noted, city-level leadership and action is crucial for reducing the impacts of dangerous climate change. Initiatives by cities, he argued, “will save lives, they'll strengthen and protect the national economies, they'll make cities more healthy and economically vibrant, and together they'll make a difference in the global fight against climate change”. The management of our cities, especially major cities like Melbourne which are moving beyond a manufacturing-based economy and experiencing rapid growth, presents a major opportunity.

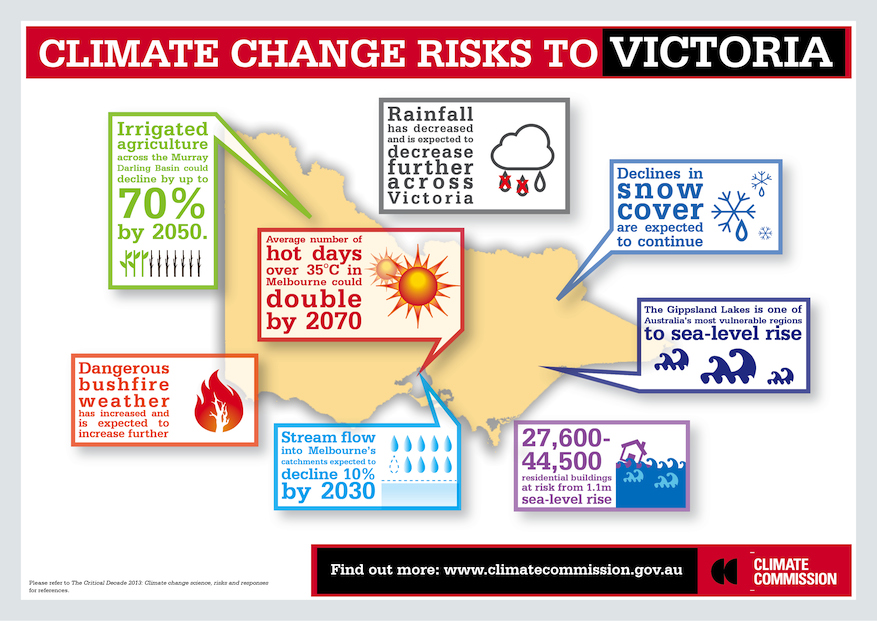

Projections of climate change for Victoria and for Melbourne were presented by CSIRO (2007) and the Department of Sustainability and Environment (2008). Average temperature in Melbourne is expected to rise, even in a “low emissions” scenario. By 2070, average temperatures in Melbourne will be around 1.0 to 2.5°C hotter than the 1990s, double to five times more warming than occurred from 1910 to 1990. The number of days above 35°C in Melbourne is projected to more than double by 2070 in a “high emissions” scenario.

Winter rainfall is estimated to drop by 12% by 2070. This could lead to reductions in average annual stream-flow of 7-35% by 2050. Increases in sea level are occurring too, and more extreme weather events, such as heat waves, frosts, floods, and droughts, are predicted.

The Victorian State Government’s metropolitan planning strategy Plan Melbourne identifies “a changing climate” as one of the key pressures facing Melbourne, but does so using highly ambiguous language without a clear need for action.

What climate change will do to Melbourne

Increases in the frequency and intensity of heat waves in Melbourne affect human health and infrastructure. They lead to increased hospital admissions for heat stress and associated illnesses, as well as increased mortality, such as was experienced in late January and early February 2009, with the heat waves leading up to the Black Saturday bushfires in Victoria.

Impacts on infrastructure include speed restrictions on the metropolitan railway lines due to bending of tracks, cancellations of trains because of failure of cooling systems, and reductions of electrical power transmission from Tasmania through BassLink. These types of infrastructure may also be vulnerable to flash flooding caused by extreme rainfall events, as well as damage caused by storms and heavy winds.

But sea-level rise is expected to be the most significant climate-change issue for coastal areas of Melbourne including the high-density cities of Melbourne and Port Phillip, due to the associated impacts of coastal erosion and storm surge. The extreme storm surge associated with a 1-in-100-year storm today potentially will become a 1-in-20 year annual storm surge event by 2070 due to sea-level rise. By 2070, inundation from a 1-in-100 year storm could affect more than 1,000 existing dwellings and property to a value of approximately $780 million. This would have impacts on high-density urban renewal areas such as Docklands and Fishermans Bend, which are only a few metres above sea level.

The best and the worst of current planning

There is increasing evidence that the biggest obstacles to rapid implementation of large-scale de-carbonisation strategies are political and social, rather than technological. Key political roadblocks include denial of the necessity and urgency of action, the influence of the fossil-fuel industry and its allies, political “short-termism”, and governance constraints.

The Victorian State Government’s metropolitan planning strategy Plan Melbourne identifies “a changing climate” as one of the key pressures facing Melbourne, but does so using highly ambiguous language without a clear need for action. It is therefore not surprising that, while Plan Melbourne includes discussion of key challenges such as energy efficiency and supply, waste management, water, and food security, it falls well short of providing a comprehensive program.

Climate change is treated as a discrete area of the plan, rather than a key principle running through other areas, such as population growth, economic productivity, and transport infrastructure. This tendency to downplay the link between climate change and extreme weather events is consistent with the ongoing reluctance of Victorian governments and authorities to fully address these linkages, for example, the failure of the recommendations of the Royal Commission into the 2009 Black Saturday Bushfires to explicitly address climate-change risks.

The City of Melbourne’s approach is significantly more promising. Its emissions reduction strategy provides a comprehensive overview of opportunities for reducing emissions across Council operations, buildings, and systems, including a “game-changing” combination of initiatives driving a rapid transition to a zero-emissions CBD comprising switching to renewable energy (50%), reducing energy used by city buildings (40%), and reducing energy lost from the grid (10%). Its climate-change adaptation strategy discusses expanding storm-water harvesting and re-use, tackling the urban heat-island effect through heat-wave response action plans, actively planning to control the consequences of sea-level rise, and developing sophisticated communication and warning systems to respond to extreme-weather events.

The City of Melbourne has also recently been selected to be a member of the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities programme. This programme will fund the creation of a Chief Resilience Officer position and provide other support to develop a resilience strategy for the whole of metropolitan Melbourne.

Other municipalities are also taking positive steps. The Cities of Moreland and Yarra have set up the Moreland Energy Foundation and the Yarra Energy Foundation, respectively. These independent not-for-profit organisations support local residents and businesses in moving towards a zero-carbon society, including by advising on and helping with the installation of solar panels and improving the energy efficiency of buildings.

Melbourne’s road to an adaptive, zero-carbon economy

There needs to be a clear and unequivocal public commitment by the Premier of Victoria and the mayors of Melbourne’s municipalities to achieve a swift transition to a just and resilient zero-carbon economy, including setting emissions reduction targets informed by the most robust and up-to-date climate science.

Climate-change action must be a key objective in the implementation of Plan Melbourne’s initiatives, tasking the Metropolitan Planning Authority with both the responsibility and power to take action, including legislated targets of zero emissions by 2020. In particular, an implementation plan for Plan Melbourne’s transport objectives must feature a greater emphasis on environmental goals, including making public transport more attractive and improving conditions for active travel (i.e. cycling and walking), as well as moving from petrol- and gas-fuelled vehicles to electric vehicles. Carbon emissions standards for all new buildings, taking into account energy use throughout their lifetimes, must be implemented, as well as programmes for retrofitting of existing buildings, including through energy-efficient heating and cooling.

The energy-related activities of the Cities of Moreland and Yarra should be scaled up to establish the Melbourne Energy Foundation, with a renewable energy plan based on the goal of achieving 100% renewable energy within 10 years. The key feature of this plan would be a rapid phase-out of all Victorian coal-fired power stations and coal mining, and an immediate end to all public subsidies and tax concessions to fossil-fuel industries. However, this would need to be complemented by support for communities affected by the phase-out of fossil-fuel-based industries, mobilisation of investment for renewable energy sources (such as wind power, solar photo-voltaics, and solar thermal), and accelerating the electrification of household and industrial heating and cooling.

It is imperative that Melbourne takes serious action on climate change, both in reducing emissions and in reducing vulnerability to the impacts of climate-change. Climate change must be seen as a key issue intrinsically bound up in the city’s wellbeing and prominent in decision-making for the city’s future. The time to act is now.

Professor John Wiseman, Deputy Director, Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute;

Professor David Karoly, Professor of Atmospheric Science, The University of Melbourne;

Alexander Sheko, Research Associate, The University of Melbourne.

This article - co-published by The Guardian (Australia) Victorian Election: The Countdown - is an edited extract from the chapter ‘Cool Melbourne: Towards a Sustainable and Resilient Zero Carbon City in a Hotter World’ in the forthcoming ebook ‘Melbourne: What Next?’ The ebook will be available for free download from the website of the Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute from 6pm on 17 October: http://tinyurl.com/melbwhatnext