(Star candidates: Jayalalitha Jayaram, left, and Hema Malini)

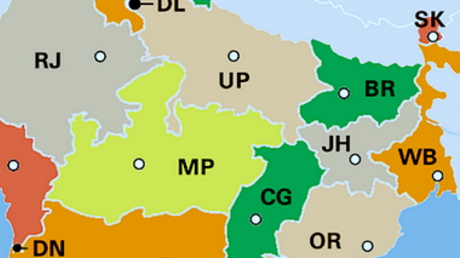

April 24 is the second-biggest voting day in India’s nine-phase election, with 117 seats up for grabs. The constituencies are located across the sub-continent, stretching from Nowgong in India’s northeast state of Assam to Anantnag in Jammu and Kashmir.

To identify a theme for such a diverse electoral landscape is difficult, but an attempt can be made perhaps by focusing on the fortunes and hopes and fears of two women from very similar backgrounds.

Hema Malini and Jayalalitha Jayaram are both Tamils born into the Iyengar Brahmin community. They both trained in classical Indian dance forms before becoming movie stars. Hema moved from her home state to Mumbai and became a leading light of the Hindi film industry. Jayalalitha did flirt with Hindi cinema but was largely confined to Chennai (earlier known as Madras), the seat of Tamil cinema.

Both would appear to be unlikely politicians. Jayalalitha has the longer and more illustrious career. She heads the AIADMK party that runs the government in Tamil Nadu. This is her third term as chief minister and she has built on the political legacy of the late M.G. Ramachandran, the founder of the AIADMK, a movie icon himself and Jayalalitha’s mentor in both films and politics.

Hema Malini is a more recent entrant to politics. She has been associated with the BJP, which nominated her to the Rajya Sabha or Upper House of Parliament a few years ago. In 2014, she has taken a risk and decided to contest a direct election – for the Lok Sabha seat of Mathura.

Mathura is a city in Uttar Pradesh, up in the northern plains of India. It is not too far from New Delhi but miles and miles away from the southern coasts of Tamil Nadu, where Hema has her origins. Mathura is a tough constituency for Hema. She is battling Jayanth Chaudhary, whose grandfather, the late Charan Singh, was once India’s prime minister. A member of the RLD, Jayanth – and his father Ajit Singh, aviation minister in India’s outgoing government – is depending on the support of his agricultural Jat community.

If India threw up a horribly hung Lok Sabha, Jayalalitha could jockey for power and maybe even get the prime minister's job in a government dominated by state and regional parties.

In that sense, Hema is an outsider and an underdog. The BJP opted to give her the nomination after it couldn’t decide between two or three local party functionaries, all of whom seemed to have a reasonable claim.

On her part, Jayalalitha is far from an outsider or an underdog. Tamil Nadu has 39 Lok Sabha seats and the neighbouring and social contiguous state of Puducherry (formerly known as Pondicherry) has one. In recent months, the AIADMK has spoken of winning 30-35 of these 40 seats and emerging as the third-largest party in the Lok Sabha – behind the BJP and the Congress.

It was for this reason that Jayalalitha refused to consider a pre-election alliance with the BJP. She wanted to keep her options open. She could join hands with the BJP after the results and become a king-making ally. Alternatively, if India threw up a horribly hung Lok Sabha, she could jockey for power and maybe even get the prime minister’s job in a government dominated by state and regional parties.

As April 24 approaches, some of this conventional wisdom is being challenged. In Mathura, Hema is more confident than she was at the beginning of her campaign, though far from certain of victory. In Tamil Nadu, the AIADMK is still the front-runner but the sort of domination that Jayalalitha expected is being questioned by opinion polls and political assessments

The reason for both sets of conflicting emotions is the same: the Narendra Modi factor. In Mathura, Hema faces a formidable incumbent. Further, she has been a listless campaigner and clearly hasn’t taken to the rough-and-tumble and heat-and-dust of hard, grassroots politics with gusto. Yet, if there is a Modi wave, as some say there is, then she could well win Mathura because a national mood will far outstrip local factors and conditions, including among Jat voters.

In Tamil Nadu, the AIADMK’s chief local rival, the DMK, was widely seen as Jayalalitha’s only concern. Now, Modi and the BJP have put together a six-party alliance of small parties and maverick politicians. Individual constituents of the alliance have influence in a few districts here and there. Added to this is an undoubted curiosity about Modi. This has made the Modi-fronted six-party grouping an unpredictable factor in Tamil Nadu elections. It can win seats, it can play a spoiler by cutting into votes of other parties, it can do both – nobody is sure.

Jayalalitha, however, is worried. From not bothering to mention Modi in the initial days of canvassing, she has taken to attacking him hard in the countdown to polling. She sees him as a threat, just as Hema – a woman Jayalalitha has so much in common with – sees Modi as an opportunity.

April 24 will determine the destiny of these strong-willed, talented Tamil women and former actors. Where else but in India would such an electoral scenario have been possible?