In about six weeks, India should begin voting for its 16th Lok Sabha, or Lower House of Parliament. With 815 million voters – more than all other democracies combined – a general election in India is the largest peace-time collaboration of a single group of human beings. It is a logistical marvel and in so many ways a miracle.

Every election, anywhere and at any time, is important and tells a story. Many elections, some genuinely and some hyperbolically, have been described as “turning points” or “historic”.

It is too early to tell whether the 2014 election in India – a month-long exercise that is expected to be completed by the middle of May – will yield to such superlatives. Nevertheless this election is worth watching.

It takes place at the intersection of two inexorable trends in Indian society – demography (a young population, getting younger) and urbanisation.

India’s tryst with economic reform can be traced to the budget speech that Manmohan Singh – the current and outgoing prime minister – delivered as finance minister in July 1991. It is commonplace to point out the generation that has been born and has come of age since 1991 has experienced an India their predecessors could only fantasise about. Equally, it is sobering to note this post-1991 generation will vote for the first time in a national election in 2014.

In April-May 2009, when the previous Lok Sabha election took place, this generation was just short of its 18th birthday and not yet eligible to vote.

The maturing of “liberalisation’s children”, if one could coin such an expression, needs to be conflated with the other trend. India’s urbanisation boom has been a by-product of liberalisation and of 22 years of up-and-down economic reform and growth. India’s cities are sprawling and disorganised, but they are far larger than they ever were and contribute much more to the economy than previously.

A pan-Indian middle-class vote is gradually emerging.

According to a McKinsey Global Institute report of 2008, urban areas contributed 58 per cent of India’s GDP that year. By 2030, Indian cities and towns will account for 70 per cent of GDP. This concentration of economic wealth and action in a few cities makes them mega-magnets for migration.

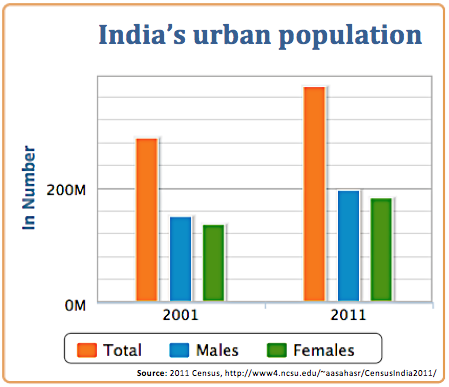

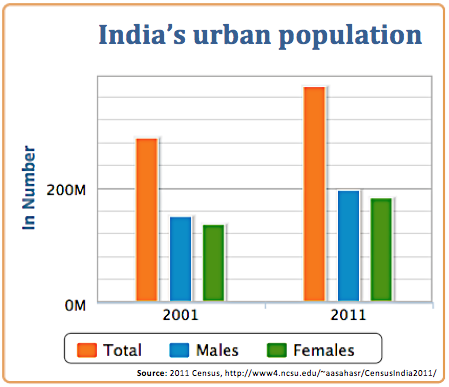

These factors are beginning to affect Indian politics. According to the 2011 Census, about 33 per cent of Indians can be classified as urban. That would imply one of every three voters is urban. However, a larger number of voters registered and voting in rural areas work in cities and towns or have economic associations with urban India.

These associations are changing lifestyles, attitudes, incomes and inevitably voting preferences. There is a creeping realisation that some problems can be solved by the local, provincial legislator or politician, perhaps one with a caste affinity; and some can be better tackled by the Union government in New Delhi. A pan-Indian middle-class vote is gradually emerging.

India is at the beginning of a process that will completely redefine its politics and could, paradoxically, make its voting patterns even more dynamic and its elections even more unpredictable. Aspects of this process were visible in 2009 and served to give the Congress a robust mandate and help it sweep urban seats.

In 2014, with the young population having grown still larger, with a still more impatient youth cohort entering the electorate, the implications can only be guessed. The impatience has been heightened by the fact that economic growth rates have halved in the past two years. India’s GDP expanded at an average of 8.3 per cent a year between 2003 and 2011; today it is creaking, held back by absence of investment and jobs, and high inflation.

It is telling and somewhat ironical that economic sentiment is so sullen even though, in absolute terms and in regard to opportunities available, there is just no comparison between the economy that India has today and that it did in 1991. Why then is the popular mood too ugly for the government to even contemplate? The answer is simple: liberalisation has spawned an expectations revolution the likes of which India has never experienced, not even in the 1950s, with the first flush of freedom and the idealistic aspirations of the Nehru era.

That is why a sharp three or four per cent decline in GDP growth rates in a matter of two years – which would have been easier to tackle, explain or distract attention from in, say, the 1970s – is today a compelling concern. It tells an army of young voters – 18 to 20 year olds – that they are not going to get as lucky as not some mythical Indian generation of 5,000 years ago but their older siblings and college seniors in the immediate past.

When dreams are shattered, it is easiest – sometimes justifiably – to point fingers at privileged orders. Children blame parents. Young voters from small towns and middle-Indian homes will blame well-entrenched elites who seem to dominate politics and business and other public institutions.

In this situation, the appeal of an outsider, a man from the country and not the gilded capital, from beyond the infrastructure of inter-connected influence and affluence, without a lineage to cushion him, an up-by-the-bootstraps achiever from nowhere, is strengthened.

In a sense – and admittedly in a very, very different society – this was the calling card of Barack Obama in 2008. In 2014, it is the appeal of both Narendra Modi of the BJP and Arvind Kejriwal of the Aam Aadmi Party. Modi represents the politics of pent-up aspiration. Kejriwal represents the politics of pent-up anger. From their vantage positions, they are both targeting the Congress, in power for so much of India’s democratic history and for 10 years running now.

Aspiration or anger: which motive force will prove stronger? We’ll know in May.