ONE THING that’s been new and noticeable in media this election cycle has been the proliferation of Fact Checking sites, like Politifact, The Conversation and the ABC’s own Fact Checking Unit. These sites are meeting a felt need: mainstream journalism has delivered mostly a choice between “he said, she said” journalism, where the competing claims of political opponents are reported without examination on the one hand, or on the other, nakedly politically partisan opinion pieces.

Fact checking sites fill a need to dig deeper into the issues, and to search out what we can know. They promise an alternative to the cacophony of all of those with partisan axes to grind—whether the politicians and lobbyists whose views are reported in the back and forth of “he said, she said“ reporting, or opinion pieces that fill column inches of the newspapers, and which fill so many political blogs. Examining the issues to find facts feels like a refreshing change.

But isn’t all this just a bit anachronistic? Aren’t we harking back to a time of greater certainty, when we treated our ‘betters’ as experts with indisputable knowledge, to whom we could defer on matters beyond our grasp? Aren‘t we buying into a naive view of knowledge, where there’s a simple undisputed field of facts that experts are able to uncover and deliver for us without dispute? Isn’t the entire phenomenon of fact checking philosophically naive in this pluralist world with a multitude of different views?

I’m glad to say that the answer to all of these worrying questions is ‘no’. The kind of fact checking these sites provide doesn’t look back to a bygone age of undisputed authority and expertise, and it doesn’t assume a philosophically naïve view of knowledge or truth.

If the history of political or philosophical debate over time has taught us anything, it’s that there is nothing that is so certain that it won’t be questioned. Debate and rationality and doesn’t work to get rid of disagreement. Instead, they can clarify it by mapping out the options with their costs and benefits. There’s no unquestionable ground from which we can all stand, and Fact Checking sites and those who find them useful don’t need to assume that there is any unquestionable ground for knowledge—Fact Checkers vary in their judgements.

Politifact called Tony Abbott’s claim that red tape has lengthened from mine approval times from 12 months to 3 years as Half True, while The Conversation rated it False. But that’s no problem—what’s important in fact-checking sites is not just the conclusion, but the way they get to their conclusion—their process of reasoning, which is shown for anyone to follow.

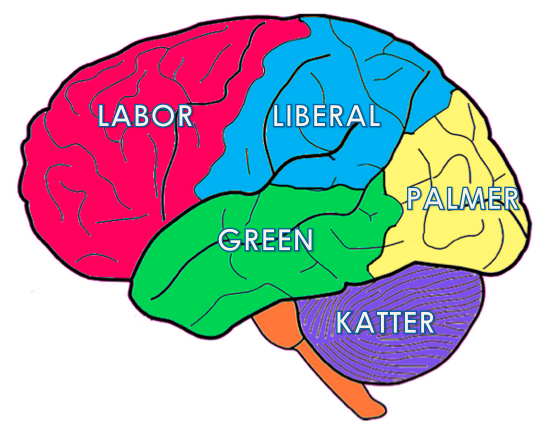

This is why fact-checking is important. When it comes to political debate, controversial claims are used as totems for one side or another. If you’re very committed to doing as much as possible to halt climate change, that’s a Green position. If you would like to use and a modest carbon price and market forces to reduce climate impacts, that’s a Labor position, and if you’d like to backpedal on those spending commitments, then this is aCoalition position. Your view on these claims just stands in for what political party you support, and “he said / she said” journalism and opinion pieces only reinforce this. But the issues are so much more important than their use as slogans that identify one side or another.

If the history of political or philosophical debate over time has taught us anything, it’s that there is nothing that is so certain that it won’t be questioned. Debate and rationality and doesn’t work to get rid of disagreement.

We should care about whether it’s true that the planet is warming, not just because we want to identify with one party or another, but because it’s our planet and our future. Claims about the economy or the environment, or about our hospitals or universities or about foreign policy, are all important not just because parties have different approaches to them, but because these are important features of the world we live in.

If politicians state that the cost of living is rising and they use this as a justification of a change in policy, we can examine not only the proposed policy, but about also the reason given for it. Is it right that cost of living is rising? If so, how? If not, why not? It’s important to understand what we can, because it’s this one world we share. We need to understand our world if we’re going to navigate it and decide how we can cooperate and live together.

Politicians very rarely give extended reasons for their policies or positions—there is little of the grand narrative in our political rhetoric. There are few attempts to explain how the policies fit together to work toward a longer-term goal. Our horizon is short term, and policy proposals are often quick fixes.

Yet when politicians give reasons for their positions, it can draw us in. One reason that the Prime Minister’s impassioned case on Q&A for same-sex marriage wasn’t only the emotion, it was the reasoning he used. He explained that his position followed from his conviction that homosexuality was normal and not aberrant—and he challenged the questioner on that point. This kind of reasoning—simply drawing out the premises underlying a position—can be helpful, not only in helping clarify what Kevin Rudd’s reasons are, but also in helping us see if we can follow along the same path to the same conclusion.

In this case the conclusion isn’t an easily testable matter of fact, but the principle is the same as in the fact checking cases. Thereasoning is important—it helps us see what’s at stake in taking up a position, not just as a totem of my party affiliation, but because of how we see the world and how the evidence leads us.

The same is true with fact checkers: it’s not their verdicts that are most important, but their reasoning—following along with their reasoning helps us see what’s involved in the claims politicians make, and that’s surely what’s important. Sometimes those reasons are complicated and we won’t come to agreement. That’s no surprise, since our world is a complicated place, and we all view it from different angles. But the better we can clarify our reasons for why we take the world to be the way we do, the better informed we’ll be when we try to judge what path to take, whether at the ballot box, or in any of the many other decisions we need to make each day.