This is an edited version of 'Budget Deficits, Business Cycles and Macroeconomic Policies'. Download the full report here.

The lay of the land

THERE CONTINUES to be a great debate around Australia’s fiscal position. Much of the discussion focuses on the Commonwealth government budget deficit. The August 2013 Pre‐Election Economic and Fiscal Outlook reports an expected (2013–14) deficit of $30 billion resulting in a deficit to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) ratio of 1.9 per cent and a public gross debt to GDP ratio of 33 per cent (roughly double the share at the onset of the global financial crisis (GFC)).

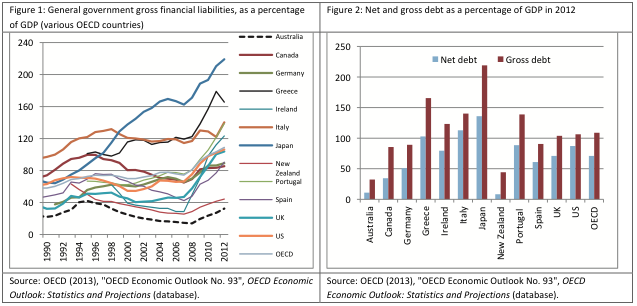

Sovereign debt is high on the agenda for a great number of policy makers around the world. This is because government debt has become very large in many developed economies. Gross debt as a share of GDP in 2012 was in excess of 100 per cent for Japan (219 per cent), Greece (166 per cent), Italy (140 per cent), Portugal (139 per cent), Ireland (123 per cent), the United States (106 per cent) and the United Kingdom (104 per cent). The OECD average in 2012 stood at 109 per cent of GDP.

Against this backdrop, the Australian debt to GDP ratio is one of the lowest in the world. Comparing Australian gross debt as a share of GDP with other countries in the OECD reveals that Australia has the lowest debt to GDP ratio; it has had the lowest ratio since 1989 — the first available data point; see Figure 1. For completeness, net and gross positions for 2012 are shown in Figure 2.

The expected 2013–14 deficit of $30 billion is also considerably lower than the deficits recorded in the wake of the financial crisis when expressed as a percentage of GDP (4.2 per cent in 2009–10, 3.4 per cent in 2010–11 and 3 per cent in 2011–12). Furthermore, the expected decline in the deficit should also slow the rise in public gross debt.

Why then should we be concerned about budget deficits? To answer this question we need to look at three issues: (i) debt service, risk and national savings; (ii) deficits as automatic stabilisers; and (iii) policy co‐ordination. Our concern is with the macroeconomic implications; specific policy initiatives in the budget statements are more appropriately evaluated by micro‐economists and industry/welfare experts.

Risk Premiums and Twin Deficits

A compelling reason to be concerned about deficits is that public debt, like all types of borrowings, has to be serviced. Interest is charged on the amount borrowed and interest charges need to be paid to avoid being caught in the trap of borrowing to pay off borrowings.

Servicing the debt has been low; since 2001 net government interest payments as a share of GDP have been below 0.5 per cent. Be that as it may, the point about borrowing is that it entails a future commitment to repay, popularly expressed as shifting the burden of the debt to the next generation. If debt is high today, Australians can reasonably expect to be faced with higher taxes or a reduction in government services in the future, unless government expenditures are directed at productivity improving investments.

The problem of servicing the debt is compounded when the economy is dependent on borrowing from foreigners. For international investors, their willingness to hold Australian debt depends on its return compared to the returns on alternative global investment opportunities, including premiums to account for currency risk (associated with an expected depreciation of the Australian exchange rate) and country risk (associated with the state of the economy).

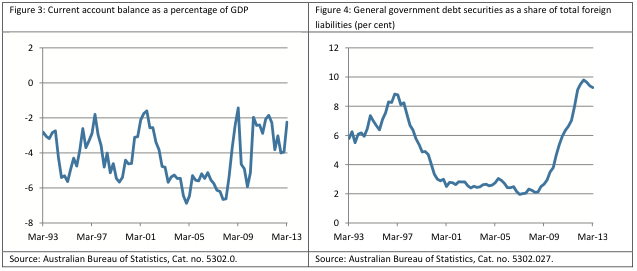

Australians have been borrowing heavily overseas as evidenced by the large and persistent current account deficit; see Figure 3. This means Australia actually has two deficits: a domestic fiscal deficit and an international current account deficit.

An economy that runs a government and a current account deficit is commonly referred to as an economy with a twin deficit. Twin deficits can present serious problems if the current account deficit is caused by the government deficit.

This is not the case in Australia. While domestic savings have been insufficient to cover private investment (hence the large inflows of foreign capital into Australia), the share of general government debt securities in total foreign liabilities is relatively small at about 10 per cent. The disturbing fact is that the share has risen from around 2 per cent prior to the GFC; see Figure 4. Put another way, holdings of Australian Commonwealth Government Bonds by non‐residents have risen from around 35 per cent in 2003 to around 70 per cent in 2013 (see <http://www.aofm.gov.au/content/investors/bonds.asp>).

Automatic Fiscal Stabilisers and the Business Cycle

Public debt evolves to accommodate changes in receipts (mainly taxes) and government expenditures. Budget balances are generally strongly cyclical. Surpluses rise during times of strong GDP growth when receipts are up and government expenditures are down. Deficits tend to occur and rise during times of economic slowdowns because receipts fall (driven by declines in income tax due to job losses) while expenditures rise (driven by increased unemployment insurance claims due to job losses).

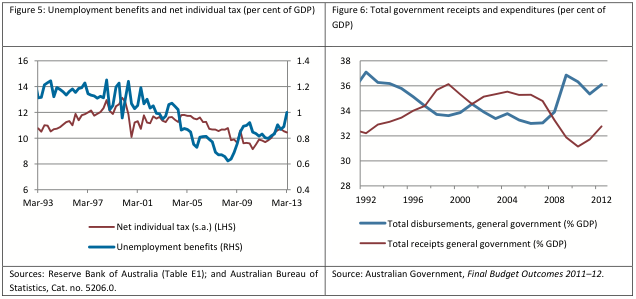

Deficits have been high during the post oil crisis recession in the 1970s, during and post the 1980s and 1990s recessions as well as during and following the GFC. Figure 5 shows the changes in net individual tax and unemployment benefits, both expressed as percentages of GDP. Unemployment benefits as a percentage of GDP rose from roughly 0.9 per cent to 1.2 per cent during both the early 1980s and the early 1990s recessions, and post GFC they rose from roughly 0.7 per cent to be about 1.0 per cent in 2013. On the asset side of the fiscal balance sheet, net individual tax as a percentage of GDP fell from roughly 12.0 per cent to 11.0 per cent during the early 1980s recession and the early 1990s recession, and during the GFC they fell roughly from 10.5 per cent in 2008 to 9.5 per cent in 2010.

In the last ten years, following surpluses of the underlying cash balance (government revenues minus government expenditures) of around 1.0 to 1.5 per cent of GDP between 2002–03 and 2007–08, the budget moved into deficit of between 2.2 and 4.2 per cent of GDP; see Figure 6. It took five years after the 1980s recession and seven years after the 1990s recession for the fiscal balance to return to surplus. It has been five years since the onset of the GFC and the budget is still in deficit.

Fiscal deficits are thus also natural outcomes of business cycles and they are important economic mechanisms that help moderate booms and busts. These automatic fiscal stabilisers counter the negative effect of job losses on consumption and mitigate the fall in GDP through increased unemployment and welfare payments. In boom times, these automatic fiscal stabilisers can potentially deliver surpluses and the debate then often becomes one of how best to use the savings.

In other words, sharp deteriorations in deficits during downturns that are driven by a combination of declining tax revenues and rising welfare expenditures need to be evaluated differently from deteriorations in deficits due to new fiscal initiatives.

Fiscal and Monetary Policy Coordination

Another compelling reason not to be fixated on the size of deficits in an environment of low growth is the potential tension with monetary policy. Policy makers usually have two levers of policy at their disposal: fiscal and monetary.

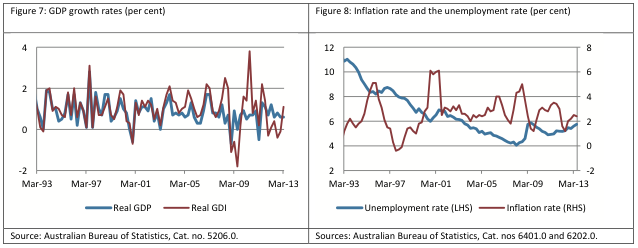

GDP growth in Australia has slowed since the June quarter of 2012 and, although some acceleration in activity is forecast, a large rebound in GDP growth in the near future is unlikely; see Figure 7 where the gap between the growth in GDP and in gross domestic income (GDI) reflects the trading gains from changes in the terms of trade. Low GDP growth has been accompanied with low employment growth which caused the unemployment rate to creep up to 5.7 per cent in June 2013, the highest rate since September 2009. As is generally the case during lower growth periods, inflation has been low and stable and well within the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) target band; see Figure 8.

The RBA’s policy objective is “to maintain price stability, full employment, and the economic prosperity and welfare of the Australian people”. To achieve these statutory objectives, the RBA has an ‘inflation target’ and seeks to keep consumer price inflation in the economy at 2–3 per cent, on average, over the medium term. Controlling inflation preserves the value of money and encourages strong and sustainable growth in the economy over the longer term (see <http://www.rba.gov.au/monetary‐policy/index.html>).

Reflecting the cyclical nature of economic activity, monetary policy is counter‐cyclical to the ebbs and flows of economic activity. In practical terms this means that the RBA typically embarks on tightening and loosening cycles. The current loosening cycle began on 2 November 2011, when the RBA started to decrease the cash rate target by 25 basis points. Since then, the RBA has decreased the cash target rate on seven additional occasions, cutting rates by a total of 200 basis points, from 4.5 per cent in November 2011 to 2.5 per cent in August 2013.

In this regard, monitoring the budget deficit is important because it is also about monitoring the stance of fiscal policy. The two components of the budget deficit — tax receipts and expenditures — represent the core instruments of fiscal policy. Acting to decrease the deficit in a climate of low growth is tantamount to adopting a tight fiscal policy. This means that both levers of policy are now working in opposite directions — tight fiscal policy and loose monetary policy. The RBA has its foot firmly on the accelerator and Treasury has its foot firmly on the brake. The outcome for the economy, as in a car, is that both actions cancel each other and just like a car, the longer it is done, the greater the likelihood of damage.

In summary

Treasury revised the 2013–14 budget deficit from an estimated $18 billion to about $30 billion. Although the change is large, the estimate is in line with the opinions of other forecasters. Over the same time period (May to July), private sector economists revised their estimated deficits from a range of zero to $18 billion in May to a range of $9 billion to $25 billion in early July to be consistent with their downward revisions to forecasts of the growth in GDP (see the report by Consensus Economics). The RBA issues monthly statements and it too has revised its forecasts as information comes to hand.

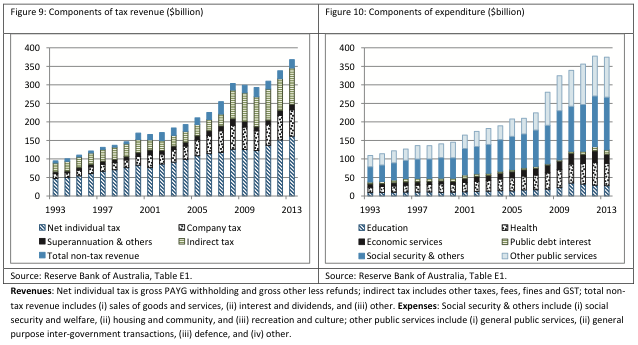

Operating a budget deficit is difficult at the best of times, and operating a deficit during an economic slowdown is especially difficult as closer scrutiny is paid to the components of revenues and expenditures. (see Figures 9 and 10 for a compositional analysis).

I have not attempted a detailed analysis of the components, except to note that whether the intertemporal decisions implied in budget decisions — spend now, build up debt and pay later — are economically sound depend on the type of expenditures.

Government expenditures directed at improving the productive capacity of the economy would lessen the burden of the debt as the investment would generate the future means to service the debt.