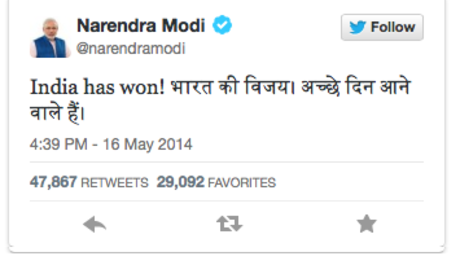

After nearly six weeks of voting, the verdict is out. Indians have thrown out the Congress-led government of Manmohan Singh in favour of the conservative Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by Narendra Modi, a controversial but charismatic politician from the state of Gujarat. By the time all the votes are counted, the BJP and its partners in the National Democratic Alliance are likely to end up winning more than 330 seats in a 545-member lower house.

The BJP alone is tipped to win around 272 seats, giving it majority control of the house, something that no single party has been able to achieve since 1984. This is a very strong performance indeed and far exceeds the party’s own expectations.

The BJP has picked up seats in almost every state, except Karnataka, where its local branch has been plagued by serious internal feuding. In the crucial Uttar Pradesh state, which sends the largest number of MPs to the national Parliament, the BJP is set to win 65 of the 80 seats, snatching 55 seats from the Congress and other regional parties.

Narendra Modi, the four-term Chief Minister of Gujarat, has never before been a member of India’s Parliament or a part of the central government. In fact, he has no direct experience of operating from New Delhi and is considered an outsider in the cliquish political and bureaucratic culture of the national capital. He is likely to rely on his trusted aides from Gujarat to manage the prime ministerial office in New Delhi.

Modi campaigned hard and pulled no punches in what can only be described as the dirtiest election campaign in India’s history. Congress was simply no match for the BJP’s highly effective, very aggressive and disciplined campaign. Congress also lacked a credible leader who could match Modi’s energy, oratory and organisational strengths.

The Italian-born Sonia Gandhi has never been able to communicate clearly with the people of India despite her improving Hindi language skills. Prime Minister Singh was not too engaged in this election campaign, having ruled himself out from the race for Prime Minister in the next government. But even if he had been actively campaigning, he could not measure up to Modi’s blistering and mocking style of speechmaking.

Rahul Gandhi, the 43-year-old scion of the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty, was the chief campaigner for the Congress. But the young Mr Gandhi is not an impressive performer when it comes to delivering speeches to large crowds. He does not have the flair of his grandmother or great grandfather. He often sounds like an angry teenager.

Even many senior leaders of his own party were embarrassed by his dismal performance in his first television interview in more than ten years. Instead of directly tackling questions about the economy, Gandhi answered almost every question by reminding the audience of the new “rights” that the Congress government had given to the people, including the right to food and right to information.

If one were to fairly judge the economic performance of the Manmohan Singh government over the entirety of its time in office, it would get at least a B+. Having delivered an unprecedented average economic growth rate of about eight per cent for seven years, the government lost direction. It could not find the right balance between promoting economic growth and ensuring distributive justice. It failed to counter the widespread perception that it had lost its way. It also never recovered from a series of corruption scandals that were very successfully exploited by its political opponents, creating a perception that the government was corrupt to the core.

The anti-corruption movement led by the octogenarian Anna Hazare and his younger lieutenant Arvind Kejriwal elevated the corruption issue to an unprecedented level in the minds of Indians. It tore the government’s credibility to pieces as a number of its ministers were charged with corruption. While Kejriwal went on to form his own Aam Admi Party (the 'common man party'), which managed to give Congress a run for its money in elections for the Delhi assembly late last year, the main beneficiary of the anti-corruption movement would now appear to the BJP. Kejriwal, who stood against Narendra Modi from the Hindu heartland of Varanasi, has lost and his party is likely to finish with three seats from Punjab. It has failed to win a single seat in Delhi, where only a few months ago it was seen as perhaps the biggest challenger to both Congress and the BJP.

Modi was parachuted into the role of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s candidate for the job of prime minister in September last year following a well-orchestrated campaign by his supporters in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the right-wing Hindu nationalist ideological mentor of the party. In nominating Modi for this position, the RSS and BJP leadership had snubbed a number of senior party leaders who have spent their careers in the national Parliament, including the Leader of the Opposition in the lower house, Sushma Swaraj.

As Prime Minister, Modi will now have to heal the wounds within his party even as he strives to live up to the heightened expectations of the people of India. He must deliver on the economic front while at the same time taming the excitable elements of the Sangh Parivar, the family of organisations of Hindu nationalists, including the RSS, who have campaigned hard for a Modi win.

This article was first published by The Conversation.