The below is a summary of Prof Reuters' presentation at the Melbourne Law School on Monday April 14. A full wrap up of that event can be found here.

Gerindra, the party of former general Prabowo Subianto - now a presidential hopeful - was the biggest winner in last week’s legislative elections, while the ruling Democrat Party of President Yudhoyono was the biggest loser.

Final results won’t be available until May, but Quick Count results suggest Gerindra won an increase in its vote of over 7%, rising from 4.4% in 2009 to 11.8%. This was an increase no other party matched, although PDI-P achieved the highest overall vote (19%) after a 4.9% increase.

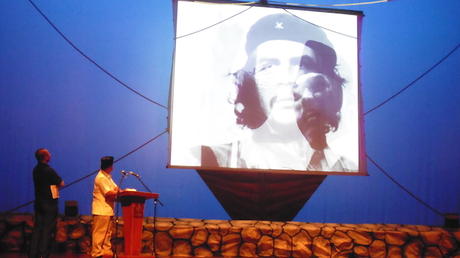

This outcome was in part because Prabowo, who comes from a wealthy family and is backed by his tycoon younger brother, was able to bankroll a heavy media presence and aggressive campaign focusing on the needs of farmers and other sectors of society left behind in Indonesia’s recent economic boom.

It is clear that large financial interests play a big part in electoral success in Indonesia. Budisantoso, founding chair of outgoing President Yudhoyono’s Democrat Party, has even claimed that ‘…elections in Indonesia are more expensive than in America’. In a country where poverty and low incomes are common, candidates need to feed and transport large crowds of supporters and fund their campaigning and party offices across a vast archipelag.

Political parties in Indonesia are essentially unable to function within the current legal framework ... as their running costs are escalating quickly.

So how do Indonesian political parties raise funds? On its own, the state’s contribution is so low as to be almost irrelevant. Legal sources – through state funding and legal private donation – usually make up only 15% of contributions. The rest must be raised from ‘other sources’, and this naturally leads to money politics or ‘transactionalism.’

Political parties in Indonesia are essentially unable to function within the current legal framework regulating public funding and private donations, as their running costs are escalating quickly. As a result, they are becoming increasingly dependent on alternative financing for their operations. Unfortunately, current reporting requirements are very weak and this makes it difficult to trace illegal contributions to political parties.

We can, however, identify a number of ways parties get access to the money they need.

The most obvious method is simply making one-off deals, with payments made in return for later favorable treatment. This has long been a source of much controversy in Indonesia, as tycoons can effectively ‘pre-purchase’ policy ahead of elections.

There are also ‘private parties’ such as Prabowo’s Gerindra and General Wiranto’s Hanura or Surya Paloh’s National Democrats, which are led by their owner/founders, and can look to them for financial backing. Of course, these are not unique to Indonesia — look at Berlusconi in Italy, or, closer to home, the Palmer United Party. In fact, it now seems Australian and Indonesian elections have at least one thing in common: billionaires running for office!

There is also the model of sewa kendaraan or ‘hiring a vehicle,’ characterized by a transactional approach to politics, by which wealthy Indonesians effectively buy leadership of existing parties. The best-known example of this is Golkar, now led by controversial tycoon, Aburizal Bakrie.

Indonesia’s leading anti-corruption institutions with responsibility in this area include the KPK (Komisi Pemberantas Korupsi) and the legislature’s own Ethics Committee. Unfortunately, these are not enough on their own to stop the institutional corruption and vote-buying that now saturates Indonesia’s political party system.

Senior politicians, such as former vice president Jusuf Kalla, acknowledge that deal-making now rules the day, and this has severely hampered the legislature’s performance and its image in the eyes of the an increasingly disillusioned public.

What can be done? Fixing these problems won’t be easy, but here are some practical suggestions:

1. Public funding of political parties should be increased significantly, but only if the following measures are also taken.

2. Free access to media coverage on all TV and radio channels, and newspapers, should be guaranteed to all parties on a quota basis.

3. Strict rules should be introduced limiting donations to parties; making both

political donors and parties liable for violations instead of pursuing only individual party members.

4. Candidates convicted of vote-buying or intimidation should be disqualified.

5. There should be strict limits set on media ownership consolidation.

6. Voter education on what can be expected from political parties in a democracy should be greatly increased.

Finally, political parties should move to (re-)establish their mass base in civil society and develop internal procedures designed to select legislative candidates on the basis of merit, rather than their capacity to pay.

This is a summary of a presentation by Professor Reuter to the University of Melbourne CILIS/ERRN seminar "Indonesian Elections: What Really Happened" (14/04/14).