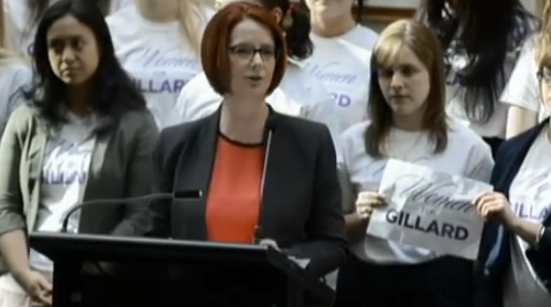

Just before Julia Gillard was replaced as Labor leader (and Prime Minister) by Kevin Rudd, she supposedly reignited the ‘gender wars’ with a speech to the Labor-affiliated group ‘Women for Gillard’. In doing so, she drew significant criticism from the media, the opposition and even members of her own party.

Drawing on themes of abortion as well as women’s representation and voice in parliament, the then Prime Minister insinuated that the election of a government led by Tony Abbott would lead to “an Australia where abortion again becomes the political plaything of men who think they know better”. She went on to characterise an Abbott-led government as replete with men in “blue ties”, arguing that a Coalition victory would leave “women once again, banished from the centre of Australia’s political life”.

It should not be such a fraught process to attempt to have a serious discussion about women’s issues in this country

The backlash that ensued was in part expected. Commentators contended that Gillard was attempting to capitalise on the support she received from women in the wake of her now famous 'misogyny speech' last year, in which she indignantly, fiercely and quite impressively tore into the opposition leader, ripping apart his record on “sexism and misogyny”. Perhaps the most surprising response, however, was that of her (male) party colleagues, several of whom declared themselves “uncomfortable” with the raising of abortion as a potential election issue.

Abortion is a contentious issue. It is polarising, emotional and difficult for many to debate. Yet it is all these things because it is important, and because proponents of both sides are deeply invested in the way it is regulated; and ultimately, it is political. For federal politicians of the governing party to suggest that debate or discussion surrounding abortion in the lead up to an election is “uncomfortable” is not only problematic, but frankly offensive to women for whom abortion is a reality, a choice or a necessity. It suggests that abortion is a guilty secret, a ‘women’s issue’ and something that should not be talked about, lest it make men feel ‘uncomfortable’.

Other electioneering or grandstanding by a politician is rarely deemed discomfiting by members of their own party. Was the speech political posturing by the then Prime Minister? Most likely. Was it an attempt to recapture some of the positive energy delivered by her “misogyny speech”? Quite possibly. Did this mean she was not passionate about a woman’s right to choose? Doubtful.

Why is ‘playing the gender card’ a distraction from policy and an obvious manoeuvre, but other political game playing is not?

It should not be such a fraught process to attempt to have a serious discussion about women’s issues in this country. Why is it that as soon as arguments are made on the basis of women’s particular needs or struggles, any subsequent arguments are dismissed, derided, trivialised? Gender is an issue. Abbott does have a bad track record on his attitudes towards women, as succinctly demonstrated by this well known advertisement from Get Up, as well as references made by Gillard in her misogyny speech. Whilst it is true that the opposition leader has claimed he will do nothing to change abortion law should there be a Coalition victory, instead leaving it to the states to regulate, can he (or the majority of politicians, really) be trusted? Whilst his promise may well be kept, especially considering commentators have suggested any change to abortion law would be too politically risky, politicians – including Abbott – have been known to change their minds.

Sure, Gillard may have introduced the abortion issue as a political move after the (limited) success of her “misogyny” speech. Was it a calculated trick? Almost certainly - but no more so than many politicians’ tricks used to push agendas on a range of social or political issues. When politicians kiss babies, visit schools, have offsiders nod behind them – these are all calculated political devices – yet we accept them as part and parcel of political campaigning.

Why is ‘playing the gender card’ a distraction from policy and an obvious manoeuvre, but other political game playing is not? Although Gillard may have brought up the gender issue in a crude manner, it is a valid concern that female voters, as well as male voters who are sympathetic to the specific challenges faced by women, should perhaps factor into their voting decision-making. The way in which a politician or a political party views women, their place in the world and the obstacles that restrict their participation in society will likely have an impact on their policymaking decisions in relevant areas. Perhaps the ‘gender wars’ are a debate we should be having.

The reality is that both sides of politics display sexist or misogynist tendencies and that these beliefs are held by a vast swathe of Australian society, male and female. In response to Gillard’s speech, the deputy opposition leader Julie Bishop came out swinging, claiming that women are no longer disadvantaged in Australia. Attacking Labor’s quota system, she argued that Coalition women (in contrast to those in the Labor ranks) are selected “on merit” and have “earned the right” to sit in parliament. However, if as Bishop asserts women are no longer disadvantaged, and the women of the Coalition are there on merit, does Bishop mean to argue that the underrepresentation of women in the Coalition (there are two women in a shadow cabinet of twenty, for example) has occurred because women do not ‘merit’ such positions of power? Is this the best representation of women that we can expect?

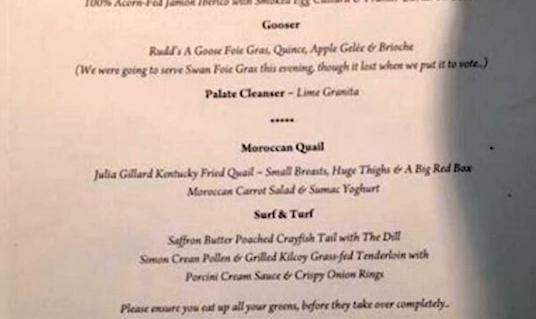

In the midst of the broad backlash against Gillard’s speech, when it appeared that the majority of the Australian media, the public and the parliament were condemning her for playing the ‘gender card’ (because women’s disadvantage represents such a strong suit to ‘play’ in the first case), mock menus emerged from a Liberal party fundraiser which used misogynist language to degrade the then Prime Minister. Advertising “Julia Gillard Kentucky Fried Quail – Small Breasts, Huge Thighs, and a Big Red Box”, the general media consensus seemed to be that Gillard was temporarily saved by the emergence of this ‘real’ gender issue to mask the ‘fake’ gender play that had backfired on her.

Unsurprisingly, senior Coalition members quickly distanced themselves from the menu, whilst the owner of the restaurant took full responsibility, claiming it was simply a joke between him and his son. However, whether it was Liberal Party sanctioned or a ‘joke’ between two ‘regular Australian men’, either way the use of this sort of language in reference to the then Prime Minister still says something about misogyny in Australia. Given such public examples of misogynist language, it is clear that issues surrounding attitudes towards women and women’s place in society should be identified and challenged. Any discussion, even if clumsily executed for political gain, as in the case of Gillard’s speech, should be welcomed as a jumping off point for a broader dialogue.

It should be noted that the Labor Party itself is by no means free from sexist attitudes. Kevin Rudd’s somewhat strange response to the menu scandal was to suggest that the Liberals should donate money raised at the fundraiser to the RSPCA. Why? Because quails everywhere were offended by being likened to a woman? In thus proving his great feminist credentials, Rudd went on to point out in response to questions about his wearing a blue tie – such as the men in blue ties referenced in Gillard’s speech – that usually his wife or daughter chooses his ties, demonstrating once again that gender stereotyping is alive and well on both sides of parliament.

The media interest in the ‘blue ties’ element of the speech was in itself baffling. It would seem clear that Gillard’s reference to blue ties was a rhetorical device employed to paint a certain picture. That it was interpreted so literally by the Australian media seems bizarre. Yet, given the Australian media frequently appears to contradict itself and concentrate on antics over policy, maybe this is unsurprising.

A meaningful discussion about the disadvantages women face .. may be Gillard’s greatest legacy, rather than the tactical, political error it was labelled

Perhaps, instead of lambasting any female political leader who raises ‘gender’ issues, we should use the rekindling of the gender debate as a starting point to talk about women’s issues more broadly – goodness knows there has been no shortage of them in the media recently. Whether it is the public incidence of intimate partner violence perpetrated against celebrity chef Nigella Lawson by her husband, and the ensuing media discussions surrounding how she ‘should’ react and whether the violence was merely ‘playful’ or the perpetrator truly meant it, alongside other incidents of victim blaming such as Serena William’s horrific comments about the young victim in the Steubenville rape case; or whether you look at the sex scandals which continue to emerge from the Australian defence force. Whether you ponder the surprisingly measured and compelling analysis of Jill Meagher’s widower, who suggested that the justice system (and society more broadly) does not take seriously acts of violence against women in the sex industry – and that perhaps it should; or whether you return to politics and review the appallingly sexist treatment of federal minister Kate Ellis on Q&A last year, it would seem that misogyny is a real issue that women have a right to be angry about. Gillard certainly experienced more than her fair share during her rocky tenure as Prime Minister; Anne Summers explains well the abuse Gillard was forced to withstand on account of her sex.

It is conceivable, then, that Gillard – as a woman, and as the much maligned and degraded first female Prime Minister of Australia – had a right to be frustrated in the face of the enduring misogyny, directed at her, at other high profile women and at women as a group, both in Australia and globally. Yes, we should be concentrating on policy rather than politics. Yes, who you vote for should be based on which party you believe will create the best future for Australia and the most secure world for it to exist in. However, if amongst the leadership speculation, incessant poll-taking, politicians posing near infrastructure, repetitive sound bites and posturing, Australia’s first female PM ignited a debate around women’s issues and inequality, was that such a bad thing?

There is so much other scripted rubbish and political manoeuvring said or done by Australian politicians and reported by the Australian media, it seems hypocritical that this particular bit of political gameswomanship elicited cries of ‘let’s talk about policy’, but other rubbish does not. As we contemplate the downfall of Julia Gillard, if we can turn the uproar about gender into a meaningful discussion about the disadvantages women face, that may be Gillard’s greatest legacy, rather than the tactical, political error it was labelled.