The Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle's (PDI-P) smaller-than-expected plurality of 19%, according to quick counts, has prompted questioning of whether there really is a Joko Widodo (Jokowi) effect at play in Indonesian politics.

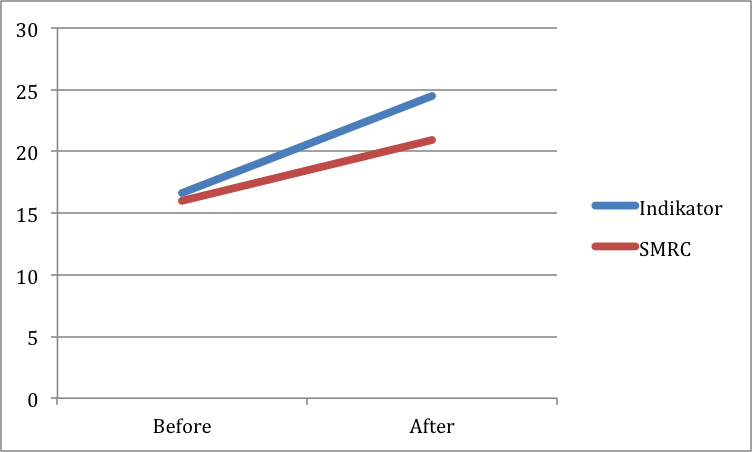

Two polls comparing PDI-P's support before and after PDI-P confirmed Joko Widodo as their presidential candidate had predicted PDI-P's vote would increase from around 16% to the low to mid twenties; the party's internal polling reportedly had it scoring higher still. Based on these publicly available polls PDI-P's support did increase following Jokowi's confirmation, but not by as much as predicted. (Although if PDI-P achieves a result of 19%, it will be within the margin of error of the SMRC poll.)

Indikator and SMRC Polls, Before and After Jokowi Confirmed as PDI-P Candidate

Why could this be the case? One explanation has been that PDI-P made ineffective use of Jokowi, for instance featuring him in their television ads only late in the campaign. For mine, that doesn't explain the variance between the survey results and PDI-P's actual vote, because any ineffective campaigning should already have been reflected in the polls.

The same problem applies to Edward Aspinall's local-level hypothesis for the variance, in which he posits that on election day voters may have chosen individual candidates who campaigned in their narrow self-interest largely independent of their parties, whereas survey institutes asked about party preferences. But based on their survey release, SMRC presented respondents with the actual ballot form from their electorate when it asked them to choose parties, and Indikator may have (their release is less clearly worded on this point). If they were able to find their preferred candidate in the right party list on polling day, they ought to have been able to find them when asked by survey institutes.

Of course, Aspinall's hypothesis could still hold if voters made their choice after these surveys were fielded, based on last minute individual campaigning. The Indikator poll was fielded on days 3-9 of the three-week campaign; SMRC on days 11-15. A change in voter preference after that point would also be consistent with the apprehension expressed by candidates and parties that last-minute money politics could change minds.

Another speculative possible reason for the variance between the surveys and the result though could be that the surveys measured the intentions of people who were never going to vote, and that these non-voters disproportionately told pollsters they were going to vote PDI-P. The SMRC question on party voting intentions had a don't know/no answer rate of 6.8%; the Indikator poll 12.4%. The no vote rate in the real election will almost certainly turn out to have been much higher - in 2009 the no show rate was 29% and some quick counts suggested a similar figure this time.

Disproportionate numbers of people whom surveys predicted would vote PDI-P not voting at all would be consistent with the very different esteem that Jokowi and parliamentarians enjoy from the general public. Again, speculatively, people may have answered when asked by pollsters that they would vote PDI-P based on affinity to Jokowi, then not voted because of their low regard for parliamentarians.

Thumbnail image resized and sourced via Flickr, user Eduardo M. C.