WHEN THE Prime Minister Kevin Rudd decided to bring the Emissions Trading Scheme forward by a year, he said it was to "help cost-of-living pressures for families and to reduce costs for small business".

"Cost of living pressure" is also a key message of Opposition leader Tony Abbott.

The implication from both leaders seems to be that the cost of living is rising. But is this true?

The Consumer Price Index

In a literal sense the cost of living is rising. The best measure of changes in the cost of living is provided by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), produced by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) on a quarterly basis.

The CPI shows the change in the price level of a (very large) basket of goods and services that reflects the composition of consumption purchases by Australian households. This has risen more or less steadily over recent years, at an average rate of just under 3% per annum.

As a consequence, goods and services now cost approximately 9% more than they did at the start of 2010, and 48% more than they did at the start of the 2000s. This is unsurprising, since it is an explicit goal of the Reserve Bank of Australia that the general price level rise by 2% - 3% each year, which implies consumer prices will rise at a similar rate.

However, it is unlikely that general price rises, or inflation, are what people have in mind when thinking about increases in the cost of living. Wages and government benefits also tend to rise over time, so the more pertinent question is whether prices are rising more rapidly than wages and benefits – or household incomes more generally. If average income is rising more quickly than prices, the basket of goods and services that the average household can afford is rising over time – that is, ‘real’ incomes are rising – and so the cost of living is effectively falling.

Household Incomes

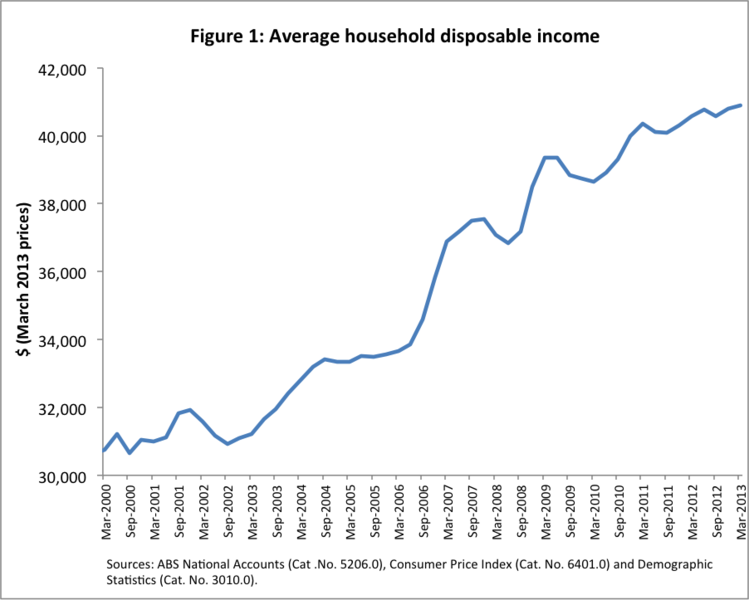

So what has been happening in Australia to real incomes? Figure 1 shows that, on average, we have been getting richer. It presents the value of total household income in Australia divided by the number of people in Australia – household income per person – with the effects of inflation removed by expressing values at March 2013 prices.

Figure 1 shows that on average living cost pressures have continued to diminish over recent years, but this is only an average, and there are certainly households that have not fared so well. This may be because the particular bundle of goods and services a household buys has increased in price more than the general price level. Since each household will purchase a different bundle of goods and services, the price rises faced by each household will probably differ, at least slightly, from the CPI.

Indeed, the ABS produces alternative versions of the CPI for different types of households in the community, including employee households, Age Pensioner households, other government transfer recipient households and self-funded retiree households. Each index measures changes in the price level for the bundle of goods and services purchased by each household type.

These indexes do in fact show that the cost of living has risen more rapidly for pensioners and other government transfer recipients over the last ten years: while the CPI has risen by 48 per cent since the December quarter of 1999, the Age Pensioner CPI has risen by 54 per cent, and the CPI for other government transfers recipients has risen by 55 per cent. For pensioners, the increase in the index is still well short of the pension increase, which was 81 per cent for couples and 100 per cent for singles over the same period. However, the benefit for the unemployed, Newstart Allowance, increased by only 52 per cent, so the real cost of living has risen slightly for this group in the community.

Households may also not have fared as well as the average shown in Figure 1 because their incomes have not risen as much as the average. For example, it may be that low-income households, or perhaps middle-income households, have not fared as well as high-income households. However, the available evidence indicates that this is not the case.

Growth in disposable incomes

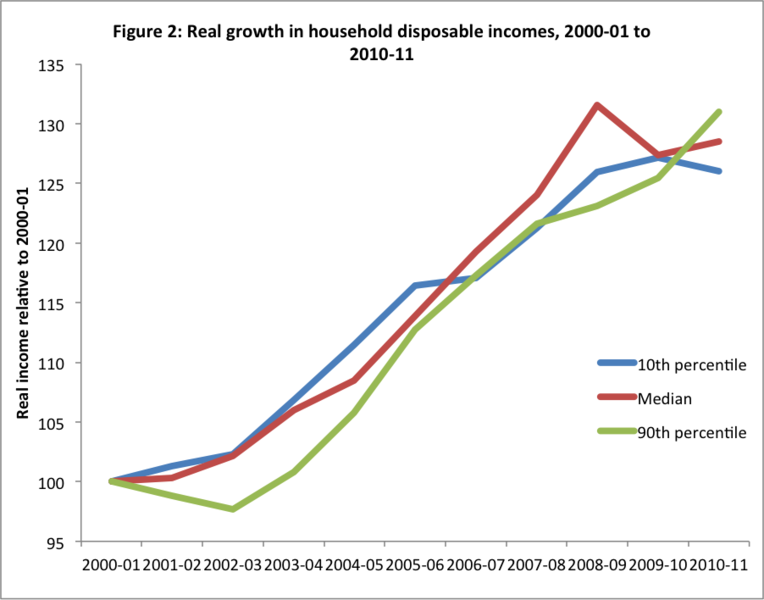

Figure 2 looks at real growth in household disposable (after taxes and benefits) income between 2000-01 and 2010-11 of low-income, middle-income and high-income households. Low-income households are defined to be those with 90% of households with higher incomes and 10% with lower incomes (the 10th percentile), middle-income households have 50% with higher incomes and 50% with lower incomes (the median) and high-income households have 10% of households with higher incomes and 90% with lower incomes (the 90th percentile).

The data, which come from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey, unfortunately stop at 2010-11, so we don’t know what has happened in the last two years, but it is clear that, over the decade to 2010-11, there has been strong income growth for all three groups.

Notes: Household income has been adjusted for household size using the OECD equivalence scale and the effects of inflation and have been removed using the CPI. Incomes are expressed relative to 2000-01 levels (2000-01 = 100). Source: HILDA Survey.

Declines are, however, evident after 2008-09 for middle-income households, and after 2009-10 for low-income households. And of course, it may well be that low- and middle-income households have experienced further declines in real incomes since 2010-11. But the broader context of substantial real growth of between 25 and 30 per cent over the decade to 2010-11 should not be forgotten.

It is therefore clear that living cost pressures are not on the rise in the Australian community as a whole

It is therefore clear that living cost pressures are not on the rise in the Australian community as a whole. This does not mean, of course, that individual households have not experienced declines in their real incomes. The experience of Newstart Allowance recipients provides one example of this, but there will be many other households who have seen their real living costs rise. Indeed, the HILDA Survey shows that approximately 40 per cent of households experience a decline in real income from one year to the next, but this is an essentially constant feature of household income dynamics. It is also true that house price growth over the last 20 years has resulted in home purchasers taking on more mortgage debt, which is is likely to contribute to a perception of increased living cost pressures among people in these households. However, house price growth, far from being a cause of falling living standards, is in fact the result of our economic success. More than any other factor, it is our rising household incomes that have caused the rise in house prices. It would be a curious logic indeed to argue that the very outcome of our rising living standards is the cause of a decline in our overall living standards.