No-one would describe News Corp Australia’s view on the National Broadband Network (NBN) as rosy.

But if it’s true the company has engaged in repeated attacks on the government because it “hates” its network, as Fairfax columnist Paul Sheehan claimed at the weekend, the big question seems fairly obvious. Why?

Shadow Communications Minister Malcolm Turnbull deserves much credit for bringing the Coalition to the policy position of supporting a national broadband network, albeit one that eschews the fibre-to-the-premises (FTTP) model being executed by Labor in favour of a fibre-to-the-node (FTTN) approach, with a reliance on existing copper infrastructure to complete the delivery of services to the home.

Turnbull rejected the crux of Sheehan’s argument: that Labor’s NBN is a greater existential threat to News Corp’s pay TV company Foxtel than the Coalition’s own policy.

On his website, he wrote a rebuttal to Sheehan’s Fairfax piece, claiming: “[t]he Coalition’s plan for the NBN will bring the day of reckoning [for the Foxtel business model] much sooner”.

Turnbull stated that Foxtel was already adapting well to the “internet threat” and repeated his claim that, by improving broadband speeds more quickly than Labor’s policy, his own approach to the NBN is hardly likely to be favoured by Foxtel or its parent company, News Corp.

All of this has led to a situation in which:

Labor is decrying Murdoch’s criticism of its NBN as being the product of vested interests the Coalition is apparently courting, rather strangely, Murdoch’s disapproval of its NBN policy as some sort of badge of legitimacy.

So, spin aside, let’s try to get some facts on the table.

What’s going on?

Telstra owns the 50% of Foxtel that News Corp does not. Foxtel enjoys a virtually unchallenged position in the provision of pay TV services largely due to Telstra’s control of the means of distribution on its hybrid fibre-coaxial (HFC) network (which combines optical fibre and coaxial cable) in the highly profitable metropolitan markets.

As the wholesale operator of what is currently the only efficient means of delivering pay TV in urban markets – an HFC network (Optus operates another) – Telstra controls the price and conditions by which any new entrant might provide a similar service to Foxtel.

This position was bolstered by Foxtel’s acquisition last year of Austar, the company which delivered pay TV to regional and rural Australia via satellite.

While it’s certainly true Foxtel suffers regulatory restrictions in Australia – primarily through anti-siphoning legislation that ensures premium sport content is offered first to free-to-air television – and that those restrictions have prevented it achieving the same levels of market penetration as it has in other countries, the company remains the only viable option for Australian viewers wishing to access pay TV.

An open, wholesale, fibre-to-the-premises NBN – the Labor version – would undermine the Foxtel business model by allowing new traditional-type pay TV providers and Internet Protocol Television (IPTV) to compete on an even playing field in the pay TV marketplace.

It is true, as Turnbull states, the Coalition’s plan will deliver faster broadband speeds nationwide – enough to support IPTV services as they currently operate – sooner than Labor’s NBN.

But this ignores the reality of broadband use in the home: there’s no allowance for the use of other applications at the same time as the operation of IPTV.

Watching and learning

Despite the over-excited claims of “tech-heads”, there’s little evidence viewers are completely abandoning “linear” (traditional, scheduled programming) TV in favour of downloading content on-demand. Rather, on-demand viewing is an additional activity to traditional TV consumption.

The viewing of news and sport, in particular, will remain an activity conducted “in real time” over traditional linear TV delivery.

If a household were, in the future, to use IPTV as its primary television provider, one must assume it would be operating constantly for several hours a day, particularly during peak viewing hours between 6pm and 11pm. This is also the time that home users of broadband are likely to be using the internet for other purposes.

Quite apart from the issue of how one family member might use bandwidth-hungry applications, such as downloading documents, running online videos, or gaming, at the same time as another family member is watching television via IPTV, the assumptions in this argument ignore the habits of TV viewers, which increasingly involve engagement with other online activity while watching television.

In a 2012 Google study, 52% of respondents indicated they were engaged with a mobile device while watching television. Presumably, in the vast majority of cases, this “multi-screen activity” relies on the home’s Wi-Fi connection over broadband.

In whose interests?

It does appear the Coalition’s FTTN model, with its more limited capacity, is more favourable to the business interests of Foxtel, particularly when one considers the interaction between the NBN and the operation of Australia’s HFC network.

Coalition policy in relation to the HFC network is unclear, stating:

Subject to an equitable re-negotiation of these provisions satisfactory to NBN Co and the government, our goal would be to remove any contractual impediments to the use of existing HFC networks for broadband and voice. A key consideration in such negotiations will be ensuring open access to networks and scope for enhanced competition in the relevant areas.

This position essentially means the ultimate structure of the HFC network will depend very much upon what Telstra agrees to in a new negotiation. That is, the Coalition appears to have committed to giving Telstra another stab at negotiating an outcome that could allow it to maintain wholesale control of the HFC network.

Turnbull has been clear that, in the interests of avoiding Labor’s “government monopoly” model and promoting competition in the provision of wholesale broadband services in those high-density urban areas in which the market can support it, Telstra would be allowed to offer wholesale broadband bundled with Foxtel services over its HFC network.

This determination to support market competition in the provision of wholesale broadband in metropolitan markets is the crux of the ideological difference between Labor and the Coalition as expressed in their approaches to broadband.

Turnbull’s appeal to the ideology of market competition sounds entirely reasonable and is in the best tradition of Liberal party economics. It is, of course, completely antithetical to the market design of Labor’s NBN, which has always been about restructuring the telecommunications market in Australia and providing equal services to regional and rural Australia by achieving structural separation of Telstra.

Turnbull has acknowledged that, for his desired outcome of wholesale competition in urban markets to work, the HFC network would have to be operated on a genuinely wholesale basis – that is, structural separation of the HFC network would have to be maintained under the Coalition plan.

The rub

The problem – and here we come to the element that has largely been ignored since Sheehan’s piece kicked off the current debate on the weekend – is that the Coalition’s policy guarantees no such thing.

In a discussion with Business Spectator’s Alan Kohler on August 1, Turnbull acknowledged that:

[o]ne possibility is that [the HFC network] is operated by Telstra as a wholesale asset, so then you would have a qualification to the structural separation objective …

To put this another way, Turnbull is admitting the possibility that the Coalition’s renegotiation with Telstra could end up allowing Telstra to be both the wholesale provider of broadband over HFC in urban areas where the HFC network currently exists and a retail provider of broadband and pay TV services over that same network.

Such a move would essentially reinstate Telstra as a vertically integrated wholesale provider of infrastructure (to compete with the NBN) and retail service provider in those markets. By providing an alternative wholesale service in only the most profitable markets, this move would almost certainly reduce the financial returns to NBN Co, raising costs that would have to be passed on to retail customers across the national network, or – more likely – result in higher prices outside the metropolitan markets.

At the same time, it will allow Telstra to, in effect, “offer” a lower wholesale access price to its own asset – Foxtel – in those profitable markets than either it, or presumably NBN Co, would make available to other retail customers.

While Turnbull admitted he was personally “uncomfortable with that” possibility, the fact remains: the Coalition policy is that, ultimately, the operation of the HFC network will be subject to a new negotiation with Telstra that could leave Telstra to operate the HFC network as a wholesale asset to its own and Foxtel’s advantage.

This outcome would be much more favourable to Telstra’s Foxtel partner, News Corp, than the current deal between Telstra and the Labor Government to decommission both the Telstra and Optus HFC networks and migrate users onto the NBN.

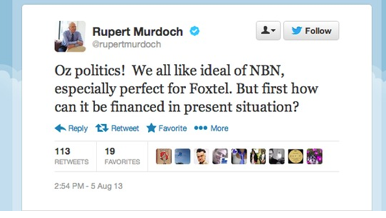

Neither Murdoch’s tweet on Monday, questioning Labor’s plan to finance the NBN, nor Foxtel’s statement this week insisting it’s in favour of fast broadband for Australia, have acknowledged these issues, choosing instead to focus on the benefit of “fast broadband networks” to Foxtel’s recent forays into mobile and on demand services.

It’s a nice attempt at misdirection, and one that leaves consumers and voters in the dark as to the real implications of the competing broadband policies for Murdoch’s business interests in Australia.

News Corp has repeatedly defended its right, as a privately-owned media company, to use its newspapers to campaign for particular policies or political parties. It also has a strong record of calling for transparency and accountability in political debate.

But in its arguments against the NBN, it would seem News Corp Australia’s campaign is less than wholly transparent in representing its own interests.

This article was originally published in The Conversation