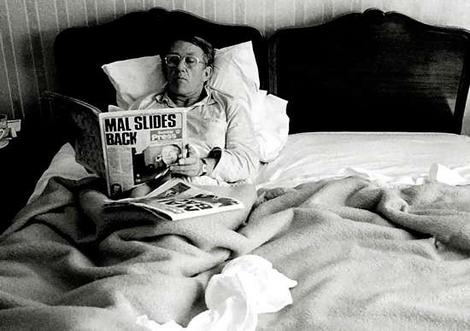

Interviewing former Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser is not for the faint-hearted. In sporting terms, the interviewer throws the ball for the subject to catch. But Malcolm Fraser switches roles, and throws a curly one. "Who are you going to vote for?" he asks.

He sits tall at his desk. It is late afternoon and he has had back-to-back meetings in his Collins Street office. Curiously, Collingwood president and Channel Nine celebrity Eddie McGuire leaves as I arrive. A colourful modern artwork hangs on the wall behind his right shoulder. It is one of several by his older sister who lives in Italy but regularly sails the Mediterranean — clearly, another Fraser octogenarian with remarkable energy.

"Tell me," he says a little more forcefully, leaning in to his large desk, "We have been through — up to 2007 — the 15 most affluent years in Australia's entire history. What has Australia got to show for it?"

This interview was intended to find out the demands of election campaigning; how it has changed over the years. It was to tease out the relationship between journalists and politicians — to understand if the media is to blame when politicians resort to sound bytes and spin rather than explaining policy as former Labor federal minister Lindsay Tanner suggests in his 2011 book Sideshow: Dumbing Down Democracy.

"You are ducking the question," says Mr Fraser. He is right. "What has Australia got to show for it?" he repeats. At that moment I have a sense of what it is like to be a freshly preselected candidate under the glare of the media spotlight unable to recall policy specifics.

But this role reversal between interviewer and subject is somewhat reflective of the rules of new media. Studies show that the most successful politicians on Twitter do not just push information out, rather, they engage in conversations.

"If I see an interesting article or someone expressing an interesting point of view I will often tweet that article." "I have seen people change their minds on Twitter"

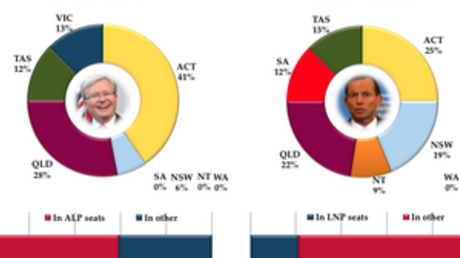

Prime Minister Kevin Rudd with 1.4 million followers and United States President Barack Obama with his 35.8 million are examples of politicians who understand the power of social media for political communication. They engage with followers rather than simply broadcast political messages.

Opposition Leader Tony Abbott, with 197,000 followers does not abide these rules, although his liberal critic, Mr Fraser does: "If I see an interesting article or someone expressing an interesting point of view I will often tweet that article." "I have seen people change their minds on Twitter."

Social media can inform the public, but he agrees it can also be an echo chamber reinforcing biases. Mr Fraser has briefly campaigned with Greens Senator Sarah Hanson-Young during this election to raise awareness about the plight of asylum seekers. He uses Twitter for this purpose too. "Boat people policy cruel: Turnbull. At least he has recognised the cruelty," he tweeted on August 19.

He says of Twitter: "there is a lot of ignorance, there is also a lot of prejudice, and some subjects bring out the prejudice very quickly. But there are also people who are genuinely searching, who ask questions."

Like many Australians, particularly Generation Y, the former Prime Minister, at age 83, no longer reads a printed newspaper, but he does read six newspapers on his iPad each day, rating The Age and New York Times as having the best online news sites. He recommends The Guardian redesign its app to make it easier to navigate.

A question often asked by media and political commentators is whether it is these endless digital deadlines, the media's insatiable appetite for news that is responsible for politicians resorting to media stunts and television-friendly one-liners to cut through the constant noise. Is the churning of news the reason why we see Tony Abbott and Kevin Rudd during this election campaign donning hard hats and high-visibility vests to lure the cameras, competing to get their messages out?

"No," says Mr Fraser. "I hold the media [only] partly responsible."

A glance at the former prime minister's election schedule from 1977 shows political leaders have always racked up flying miles traversing Australia during campaigns. Like now, from morning until night, their days were filled with speaking functions, shopping centre and school visits.

Mr Fraser says campaigning is always tough, but in the past it was less scripted. "The campaigns were not anywhere near as tightly controlled as they are now. You had a policy speech at the beginning of the campaign and you stuck to it — if you had any sense."

"You tried to show what things were going to cost and what they weren't going to cost, and that was all out in the open."

He says politicians were more transparent with their policies and costings. "You tried to show what things were going to cost and what they weren't going to cost, and that was all out in the open." Mr Fraser is disappointed that federal budgets have become harder to understand because of different reporting standards and reliance on future estimates: "All of which makes it easier for politicians really to not say what they are promising, or not promising," he says downheartedly.

"Campaigning was quite exhausting really and it didn’t necessarily have many humorous moments about it," he recalls. But, he does remember one moment of levity. "One person at Bondi who was carrying a great big banner on top of a bit of four-by-two supporting Gough (or opposing me anyway) tripped," he recalls with a smile. "It appeared as though the bit of wood had hit Tammy [Fraser, his wife]," he says. Luckily, it missed. "The photographers had caught Tammy nearly being hit and it was one little bit of publicity that was totally unmeant, you could never have staged it…[he laughs] I suppose that was a humorous moment, especially because the guy was so very upset - it wasn't his fault he had tripped."

He adds: "I would hate to be involved in the sort of tightly controlled regimented campaigns now." There are no great speeches and the debates are boring, he observes: "Kevin Rudd speaks more smoothly, but he speaks too much."

"Political leaders denigrate themselves by what they do, the things they debate and the things they don’t debate."

A famous study of newspaper coverage of America's State of the Union address from the 1790s until 1970s found politics shaped the narrative of media coverage more so than the opposite. The study showed US campaigns focused heavily on the president not because of the arrival of television — as first thought — but because through politics the president's role became more powerful over time.

Mr Fraser also emphasises political discourse above media coverage to explain how leaders and political parties have changed in Australia: "Political leaders denigrate themselves by what they do, the things they debate and the things they don’t debate."

Media coverage of Australian politics also heavily focuses on the leader. Mr Fraser believes that leaders such as Kevin Rudd, who are regularly pictured taking 'selfies' with the public, feed the media's obsession with the cult of personality.

Politics has changed too. "In my time, if I tried to intervene in a preselection the party would do the opposite. It was the nature of the party." Preselections belong to the electorate, not the leader, he says. "Once you get to a situation where a leader can determine who goes into a seat, you destroy the party. Because the grass roots, really the only real substantial function they have is to select the candidate. If you destroy that, what is left?"

Mr Fraser strongly criticises past members of parliament who think they can influence political selections and choose their successor. "It happens in both parties. What you want in parliament is not people who will do what they say. You want people who are independent, who can make up their own minds, who do have a capacity to make a judgment." It is not right for a leader to determine what subject gets a conscience vote, he argues. "Your conscience is yours. On things that are genuinely a matter of conscience such as same-sex marriage, abortion or whatever, if the party is going to say you have to vote this way or that way, to hell with them," Mr Fraser says, raising his voice. "It would never have happened in earlier times."

He says part of the problem is also that Australia's media is too concentrated and too few voices are heard. "It was [Paul] Keating's decisions that led to the destruction of Fairfax. They were probably the worst decisions he made," he says.

"In my term, there were seven print proprietors. Now there is one and a bit. We have the most concentrated media in any democratic country, anywhere in the entire damn world. That is dangerous."

"It has nothing to do with Rupert. It is the policies of successive governments that led to this situation."

During his time as opposition leader, Mr Fraser courted the media. In 1975 when he was blocking supply in the Senate, which led to the Constitutional crisis and the sacking of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, Mr Fraser had a telephone conversation with his childhood acquaintance Rupert Murdoch seeking his support. Only three years before, Murdoch had supported the election of Gough Whitlam.

Research shows that media barons like Mr Murdoch generally tend to use their media to favour one party over another for economic reasons rather than personal ideology. Among Australia's capital city daily newspapers, which are influential in setting the news agenda, Murdoch's mastheads account for 65% of circulation. In the 2013 election campaign some of his newspapers have bluntly called on voters to turn against Kevin Rudd's government with front-page headlines: "Kick This Mob Out" — a media hostility not seen in federal politics since the end of the Whitlam government.

When asked if Rupert Murdoch hinders Australian democracy, Mr Fraser shakes his head. "It is not a question of Rupert Murdoch, it is a question of whether you can afford to have a democracy with only one newspaper proprietor. It has nothing to do with Rupert. It is the policies of successive governments that led to this situation."

Mr Fraser warns we should not be complacent about the importance of a diverse media. He predicts that if Tony Abbott wins the September 7 ballot, privatisation of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation will be on the agenda. So too will closing down the multicultural broadcaster, SBS – which was created by Mr Fraser’s government in 1978. "I would be prepared to bet now that if they don’t [privatise the ABC] they will say, as a result of financial stringency, that they have to abolish SBS," he says. "We are all the losers in today's environment."