India has been proudly at the vanguard of polling technology, introducing electronic voting machines (EVMs) throughout the nation for the 2004 national election.

The machines were heralded as “fully tamper-proof”, perfectly private and resistant to ballot stuffing. They promised a single-stroke technological solution to the corruption, intimidation, skullduggery and overwhelming logistical problems of managing the world’s biggest electorate – this year with more than 814 million people entitled to vote.

Or were they?

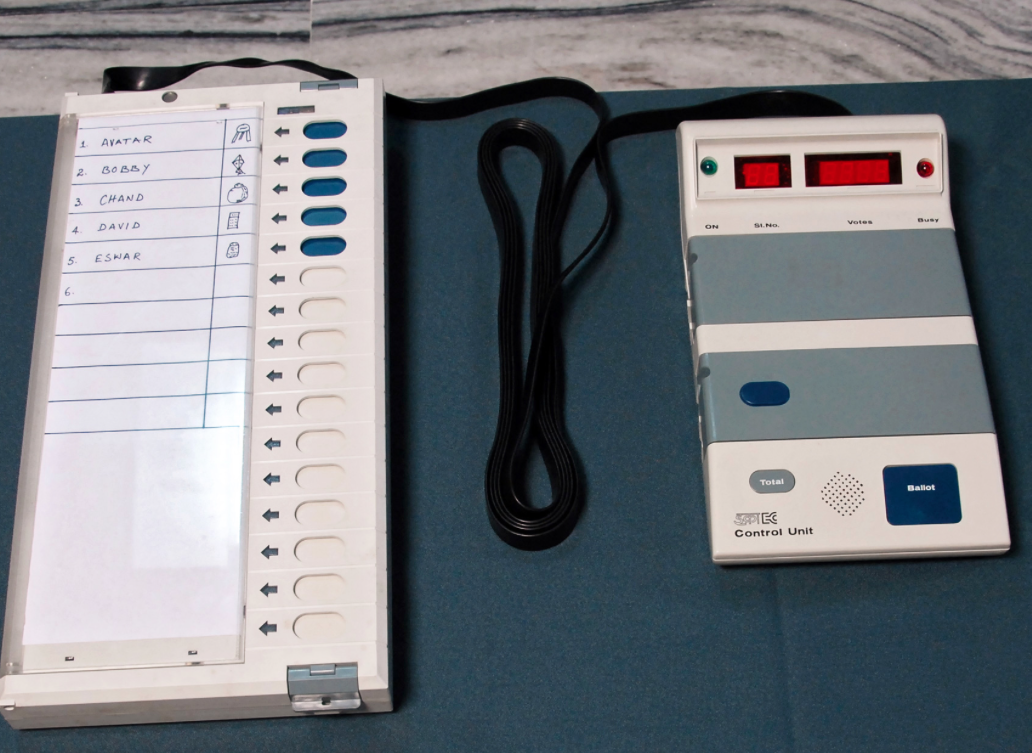

The machines were extremely simple devices with a series of buttons, one for each candidate, each with a matching indicator light that would illuminate when that candidate was selected. The voting machine was attached to a control unit that reported the tallies at the end of polling day. Although the design was simple, the machines produced no evidence that the final tally matched the votes that had been cast.

The machines were extremely simple devices with a series of buttons, one for each candidate, each with a matching indicator light that would illuminate when that candidate was selected. The voting machine was attached to a control unit that reported the tallies at the end of polling day. Although the design was simple, the machines produced no evidence that the final tally matched the votes that had been cast.

In 2009, an international team of security researchers obtained a machine and set about investigating just how difficult it really was bring off the appearance of proper operation while actually manipulating the votes. (You can read the academic paper here or see the video here) . They pointed out that the software on the machines was installed (by US and Japanese manufacturers) in such a way that it was almost impossible to check whether the result was authentic. They then considered a variety of methods of manipulating the hardware as well.

Some of the study’s authors had been motivated to challenge the technology when they discovered that not everyone believed the machines were perfectly tamper-proof.

They demonstrated a “dishonest display attack” which simply substituted the researcher’s manipulated display for the true one on the control unit. They bought some red display screens that looked exactly like the real ones, reprogrammed them to display an election result of their own choosing, and then unscrewed the control unit’s cover and placed their own misleading display in the machine. The modified machine looked exactly the same as the original, but it ignored the votes that had been cast and recorded, and displayed the researchers’ preprogrammed results instead. (The cheating device carefully kept a count of how many votes had really been cast, and generated the correct number of manipulated votes.)

They also built a vote-manipulating tool about the size of a clothes peg. The tool needed to be clipped onto the two chips that stored the votes inside the machine. Then it could read and change the votes electronically, including stuffing the ballot, and could be reused to attack numerous machines.

Some of the study’s authors had been motivated to challenge the technology when they discovered that not everyone believed the machines were perfectly tamper-proof:

“Hari Prasad, a coauthor of this study, was approached in October 2009 by representatives of a prominent regional party who offered to pay for his technical assistance fixing elections. They were promptly and sternly refused.”

Surprisingly, the security researchers were not initially thanked for their helpful insights. (As this video of the Indian election commissions’s response shows.) An Indian man suspected of supplying the machine for the security research was arrested.

Meanwhile many Indians complained that they had experienced technical problems when they tried to vote. One author collected reports of suspicious incidents from all over the country, putting together a dossier including observations such as “when the voters pressed the button to vote for one party, the light flashed on another”.

Many Indians called for a return to old-fashioned paper voting, or at least for a Voter-Verifiable Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT). The machines would be modified to print a paper record of the vote for each voter to check, then the paper record would be automatically deposited into a box. The paper records could be counted or audited if the electronic tally was not trusted. Similar designs had been implemented in the USA in response to widespread distrust of their electronic-only voting machines.

All of this eventually culminated in a successful application to the Indian Supreme Court, which ruled that all Indian EVMs should be equipped with a human-readable paper record of the vote. The court observed that:

“the ‘paper trail’ is an indispensable requirement of free and fair elections. The confidence of the voters in the EVMs can be achieved only with the introduction of the ‘paper trail’.”

The Indian electoral commission is planning to implement this change through most (but not all) of the country in time for the 2014 general election. It’s true that dealing with paper trails or other methods of demonstrating integrity can be logistically challenging, and it will be interesting to see how the Indian Electoral Commission manages their 1 million VVPAT-equipped polling places.

From the Indian experience, Australians can take three valuable lessons:

- Introducing computers does not necessarily make elections more accurate, private or hard to manipulate;

- A system may be widely believed by officials and the public to be secure, and may come with repeated assurances about its trustworthiness, but actually have serious vulnerabilities;

- The kind of transparent evidence that is built into our paper-based processes needs to be carefully designed into electronic processes too.

(Acknowledgements: Thanks to Dr Udaya Parampalli for helpful comments on this article.)