University of Melbourne health economist Dr Terence Chen's report finds the current 30% means-tested rebate is "expensive and fiscally unsustainable".

You can listen to an interview with Dr Chen below, read his analysis or view the complete report.

Policy context

Rising expenditure on health care is expected to put significant pressure on public spending in Australia. The Intergenerational Report 2010 projects that government spending on health care, as a proportion of Australia’s gross domestic product, is expected to increase from 4.0 percent in 2009–10 to 7.1 percent in 2049–50.

This growth is driven by population ageing, innovation in medical technology, and growing expectations by Australians for high quality health care. This presents an immediate challenge for the government to identify ways to extract maximum value from the health dollars it spends if it is to achieve fiscal sustainability in the longer term.

There has been some progress towards fiscal sustainability by the successful introduction of means testing for private health insurance rebates and the Medicare Levy Surcharge. This was after two failed attempts to pass the required legislation through parliament in 2009 and 2011.

The introduction of means testing was not without controversy. Representatives of the private health insurance industry strongly opposed the measure, warning about the catastrophic consequences on the public hospital system. This vastly contrasted with the modelling undertaken by the Commonwealth Treasury, predicting that the means-test will have little impact on private health insurance coverage,

The current 30% means-tested rebate is expensive and fiscally unsustainable.

Are subsidies likely to generate cost savings?

Internationally, there is some evidence from the UK and Spain that the cost of subsidising private health insurance exceeds the fiscal benefits to the public sector. A reason why this is the case is that individuals are not very price sensitive when it comes to buying health insurance.

Hence a subsidy needs to be sufficiently generous (and expensive) if individuals are to be encouraged to take up private cover. Recent evidence has shown that Australians are generally not responsive to changes in the price of insurance (e.g. Butler 1999; Frech et al. 2003; Ellis and Savage 2008).

There are a number of reasons why private health insurance in Australia is expected to have small cost-shifting effects. First, private hospitals usually manage patients with comparatively straightforward medical conditions, leaving public hospitals to be responsible for those who require complex and potentially expensive care.

Second, Australians with private health insurance can, and do, continue to use the public system. Third, because doctors can work in both public and private sectors, expanding the role of private insurance can potentially worsen the burden on the public hospital system if doctors leave the public sector for the private sector.

Modelling the impact of reducing rebates

Econometric modelling conducted at the Melbourne Institute shows that reducing rebates is likely to result in net public sector savings. The modelling uses data from Wave 4 (2004) of the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey.

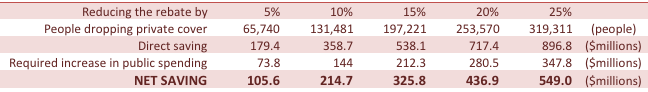

The modelling projections show that a 10 percent reduction in premium rebates is expected to lead to a 1.4 percent decrease in the proportion of the Australian population with private health insurance. Based on membership data in 2007-08, this translates to roughly 131,500 Australians dropping private coverage.

Using expenditure data in 2007-08, the predicted decrease in the number of privately insured individuals is expected to increase total public expenditure on hospital care by $144 million, as more Australians rely on the public system for their health care needs. On the other hand, government expenditure on premium rebates is expected to decrease by $359 million. Hence, a 10 percent reduction in premium rebates is expected to generate savings of $215 million.

On the whole, savings from reducing spending on rebates outweigh the predicted increase in public hospital costs by a factor of roughly 2.5.

Discussion

Australians demonstrate strong support for maintaining the mixed public and private model of financing. Given that Australians value the benefits of having the choice of private care, it is probably reasonable that they pay for this choice. The issue here is why the government should subsidise individuals to buy private health insurance.

Means testing of rebates is a positive first step and it would therefore be important to evaluate the impact of means testing. The gradual removal of rebates would be a logical and fiscally responsible next step. This should not happen quickly as the public hospital system currently has a fixed capacity and workforce which would require time to expand.

It is essential that the savings generated from means testing be wisely invested into the public hospital system to ensure public hospitals have additional resources to expand their capacity.

There are few clear ways of substantially reducing the growth of health expenditures whilst at least maintaining or even improving health outcomes. New evidence suggests that there is potential to reap significant savings by reducing the price that Australians pay for generic drugs, which is one of the highest in the world.

Revisiting the question of whether rebates should be gradually removed is one such policy that can generate cost savings to be re-invested directly back into the health care system.