As the mind-numbing debate about costings threatens to swallow up the last week of the 2013 federal election campaign, voters are entitled to ask: Is there a better way? The answer is yes. And it is not that hard to achieve.

The release of a detailed breakdown of the cost of promises made by our political leaders is important for a healthy democracy. Voters should know the true cost of the policies on offer so they can cast an informed vote. But in recent elections the process for costing policies has descended into high farce, leaving voters confused and turned off the campaign at a critical time.

This sad situation arises despite two major reforms over the past 15 years aimed at bringing budget honesty into Australian federal elections.

The parties have shown a disdain for the Charter of Budget Honesty and the extra resources made available to them through the PBO

In 1998 the Charter of Budget Honesty was introduced by the Howard government with the objective of ending the era of politicians making wild and unaffordable promises at election time. The charter made a valuable contribution in two ways: it required the government to release in the early days of the campaign updated budget figures; and it allows the parties to give the departments of Treasury and Finance their election promises for costing during the campaign period.

The charter does not compel the parties to participate in this process. Instead it is hoped they will participate voluntarily, albeit with the public pressure of being clobbered if they try to avoid scrutiny.

The second major reform came in 2012 when the Gillard government established the Parliamentary Budget Office. The PBO was intended to improve budget honesty by allowing opposition parties to have their promises costed by an independent expert team at any time during the parliamentary term.

Opposition parties do not have access to the resources of parties in government so the PBO was meant to level the playing field and lead to better-quality costed promises by all come election time.

Despite good intentions, these reforms have failed. In the 2007 election, the ALP submitted its policies to Treasury late and then waited until the Friday before polling day to release its costings. This was designed to avoid media and opposition scrutiny as well as a paid advertising assault by the Coalition (the advertising blackout begins on the Wednesday before an election).

In the 2010 election, Labor released a running total of the cost of its commitments. Interestingly, this has not been continued in this campaign. By contrast, the Coalition refused to submit its policies to Treasury in 2010 and only relented post election as part of the negotiations with the independents. This then revealed the infamous $11 billion black hole.

In the 2013 election, the Coalition has taken advantage of the new resources available to it through the PBO and submitted more than 200 policy commitments for costing. But with less than a week to polling day the Coalition has inexplicably refused to release a single PBO costing. Nor has it submitted a single policy to Treasury for costing.

The Charter of Budget Honesty should be amended to require the parties to release the cost of their election policies as reviewed by Treasury and Finance at least 10 days before the election

Take the Coalition's so-called direct action plan that commits $3 billion to cutting carbon emissions to meet the bipartisan reduction target. No serious policy analyst thinks the Coalition can reach the target with its current policy approach and funding level. But the Coalition is refusing to release a PBO costing for its climate change plan and has not submitted the policy to Treasury.

Similarly, the Coalition has attacked Labor for the past six years over its failure to release a business case for the national broadband network. Yet it has failed to submit its alternative plan to the PBO or to Treasury.

Meanwhile, Labor has had Treasury, Finance and the PBO cost a series of initiatives that it had no intention of pursuing itself but thought the Coalition might. This was not part of a policy development process but an election tactic to expose the opposition. The tactic backfired when the departments and PBO issued statements saying Labor had misrepresented their findings.

In short, the parties have shown a disdain for the Charter of Budget Honesty and the extra resources made available to them through the PBO. Where tactical gain can be made, they submit policies late or not at all. In this campaign the Coalition has clearly made the calculation that it is better off enduring public criticism but avoiding scrutiny by dumping hundreds of spending and revenue initiatives in the last hours of the campaign.

The parties have worked out how to game the system. This circus has got to stop. The architecture of the system is sound, but voluntary participation has not worked. A firmer hand is needed.

A very simple reform could radically change things. The Charter of Budget Honesty should be amended to require the parties to release the cost of their election policies as reviewed by Treasury and Finance at least 10 days before the election. This could be achieved by asking Treasury and Finance to release a report on the cost of each party's promises at this point of the campaign. The analysis would be based on whatever details are submitted by the parties, or whatever information is publicly available.

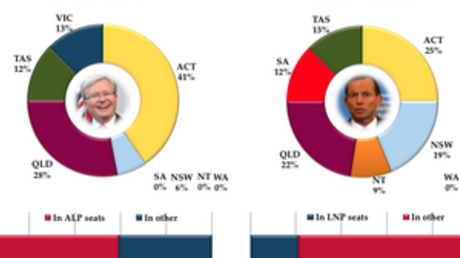

The publication of this independent report would compel the parties to substantiate their costings of their promises. To do otherwise would bring their leader into conflict with Treasury - and as Tony Abbott learnt in 2010 and Kevin Rudd is learning now, this will result in the politician coming off second best.

The establishment of the PBO makes it reasonable and possible for both major parties to comply with this new arrangement. The release of such a report 10 days before election day would provide enough time for public consideration of the parties' promises. And best of all, this reform would make our elections more honest and interesting - and enable other important policy debates to get the attention they deserve.

This article first appeared in The Age, 1/9/13