THE COALITION has at long last released its policy for schools. Unfortunately, most of the commentary has focused on where the policy was announced (see here and here) – a private, Pentecostal Christian school in western Sydney that requires students’ families to sign a pledge stating homosexuality is an abomination – rather than on the policy content.

The centerpiece of the Coalition’s policy is a $70 million fund to assist up to 25 per cent of Australia’s public schools to become Independent Public Schools, a policy hinted at in their Real Solution campaign document back in January but not clearly explained until now.

What are Independent Public Schools?

Independent public schools are public schools with large or full autonomy over their budget, staffing decisions and, to a lesser degree, curriculum.

The Coalition’s policy is based on a recent initiative of the Western Australian government. A similar ‘self-managing schools’ model was introduced to Victorian public schools two decades ago, which devolved 93 per cent of the state’s public education budget to individual schools, effectively allowing them to govern themselves within a state accountability framework.

In both models, schools get a “one line” or “global budget” based upon their school population, location and needs, which they can spend as they see fit. Instead of having teachers and other staff allocated to them, schools choose their own staff and pay them from this budget. These public schools continue to be fully government funded (though are encouraged to fundraise) and are not allowed to charge compulsory fees and cannot be selective about the enrolment of students within their catchment zones.

In other words, independent or self-managing public schools remain as state government schools, but the way the school operates more closely resembles that of a private school.

While contentious, the push to give schools greater autonomy over their budgets, staffing, strategy and curriculum dates back at least forty years and was a central recommendation of the 1973 Karmel Report which heralded the debut of recurrent funding to all schools under the Whitlam government.

Increased powers for public schools and their principals was a recommendation of the landmark Gonski Review of School Funding, is a key plank of Labor’s National Plan for School Improvement, and was part of both Labor and the Coalition’s education policy platforms at the last federal election. It has already been pursued, in varying degrees, by every state and territory government over the past four decades."

The policy is predicated on the belief that school communities have a better idea than bureaucrats of what their school needs, and that greater school autonomy enhances accountability between teachers, principles, students and families. It is also thought to enhance student and family engagement, and the school’s ability to meet the particular needs of its students, which contributes to better performance.

The results?

But the evidence on the results of greatly enhanced school autonomy is ambiguous. Even the most ardent academic advocates of this reform refrain from unequivocal claims that autonomy necessarily leads to improved learning outcomes.

A recent study by the University of Melbourne of Western Australia’s independent public schools voiced muted support for the policy, stating overall, ‘it had a positive effect on the public school system by raising its profile and contributing to a sense of renewal and positive reform.’

This study found that the despite the increased workload, the majority of principals were enthusiastic in their support of the scheme and believed it had ‘considerably enhanced the functioning of their school’ and would ‘lead to increased outcomes for the school community’. Teachers reported increased collaboration and felt more professional and in control of their careers, though a minority felt otherwise. Principals, teachers and the school community all spoke of more tailored support for students, and greater school pride. Some schools communities also reported greater collaboration and sharing of resources with other schools, to their mutual benefit.

Studies of the Victorian governments Schools of the Future devolution reforms dating back to the early 1990s report similar findings. Despite higher stress and workloads, most schools felt the reforms were beneficial overall and did not want to return to the previous model where they lacked power over staffing, budget and strategies. By 2009, Victoria had the highest average student performance, highest school retention rates and lowest per pupil expenditure of all the states, a turn-around from the situation immediately before the reforms.

But correlation and causation are two different things, and Victoria’s turn-around could be attributed to a combination of factors. It must also be noted that New South Wales has roughly equivalent academic results – the two states are “neck and neck” in recent years, despite the latter possessing a highly centralized school system and minimal school autonomy compared to Victoria.

Furthermore, while some schools thrive with their new independence, reaching new heights in academic performance and student engagement, others stagnate. The reform can exacerbate the existing divide between flourishing and flailing schools.

The success of school autonomy reforms such as independent public schools is dependent on how the reform is implemented, the capacity of a school’s leadership team, the degree of community and teacher engagement and support for the change, and the external support systems made available to the school during and after transition, including provision of additional training and financial assistance if necessary.

The evaluative review by the University of Melbourne emphasized that the complexity of school and system change cannot be underestimated.

There is no one size fits all model for school improvement. The readiness of schools to take on additional autonomy varies. If pursued, tailored support must be provided.

Independent Public Schools is a beguiling reform but no panacea.

Here are some other things you should know about the Coalition’s schools policy.

“No school funding cut” but there’ll be no large increase in “Gonski” funding either

The Coalition promises stable school funding. There will be “no cut” to funding under a government they form.

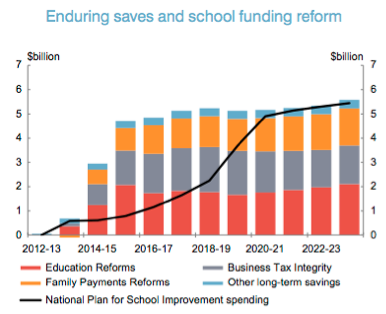

But they have only pledged to match Labor’s funding commitments for the next four years. The catch is that most of the “Gonski” needs-based funding increases come after the first four years (after the official forward estimates), as this graph from page 15 of the Labor Government’s Budget 2013-14 National Plan for School Improvement brochure illustrates.

So while not technically “cutting” school funding, their policy and rhetoric suggests that schools would receive vastly less funding in years 2018 and beyond under a Coalition government than what Labor is offering. Schools that would lose the most are small or remote schools, and those with the largest numbers of students from disadvantaged backgrounds (overwhelmingly public schools) which would have received the greatest amount of “loadings” under the Labor government’s new funding system, the Schooling Resource Standard.

“Ending the control from Canberra” … or not

The Coalition has pledged to amend the Australian Education Act (aka “Gonski legislation” to remove any parts that allow the Commonwealth government to dictate what states and territories must do in their schools, and promise that there will be no extra red-tape or bureaucracy. The states and territories’ responsibility and autonomy in school education, we are told, will be respected.

This would be wonderful but I am not holding my breath. Every Commonwealth government since Menzies – both Labor and Coalition – have increased their involvement in school education through tied grants and an ever-expanding array of programs and punitive regulations. This was particularly the case under the Howard Government’s Learning Through Choice and Opportunity legislation, where state governments attacked the Commonwealth for proceeding unilaterally in developing and imposing tougher conditions for school funding grants.

Governments of all stripes are unwilling to relinquish control, especially over such an electorally potent/popular sphere. Returning more power to states over schooling would be welcome but unexpected.

In sum, the Coalition’s policy proposal is a mixed bag that offers no new ideas and only $120 million in additional funding, of which more than half is for the Independent Public School Initiative. This far less than what the Labor has promised, albeit this promise is for a distant six years. The history of school funding, school reforms and intergovernmental relations has much to teach governments of all parties and levels, but it is unclear whether they are learning the lessons.