YESTERDAY, KEVIN Rudd set about outlining the broad terrain of economic policy to be pursued in this his second stint as Prime Minister. In his speech to the Press Club, the PM highlighted seven core drivers, which in his view will allow us to negotiate a new future after the mining boom: lowering electricity prices; freeing up rigidities in the labour market; improving business productivity; lowering the regulatory burden on business; improving education, skill and training; investment in infrastructure; and improving the operating environment for small business.

All of these are ambitious and worthy economic policy objectives. But they could hardly be described as setting a new agenda.

This speech marks an ongoing strategy intended to set the terms of the political debate for this coming election. Some of this effort is clearly intended to outplay Tony Abbott’s own attempt to do just that with his own industrial relations policy agenda, released just a few weeks ago.

The “new agenda” speech can also be read as an attempt to to reach out to key constituencies: marginal voters, the major employer groups, unions, and small business. These are the very groups perceived to be alienated by this government, which Labor must win over if it is to regain office.

There are four observations that allow us to understand why this mix of items is now top of this government’s economic policy agenda to win the next election.

Observation 1: Labor needs to reclaim the economic debate

First and foremost, this speech represents an attempt to claim the legitimacy of the policy agenda started in his first term as PM: re-inventing the Australian economy for a post-mining boom economy. But this claim, of course, is not entirely accurate. While the prospects for future growth in the world economy were already making the headlines, preparing for the end of a mining boom was hardly a major election issue in 2007. Winding back WorkChoices, dealing with the great moral imperative of our time (remember global warming?), health and education funding – these were the issues of the day, not productivity and competitiveness.

Notwithstanding an attempt to link this agenda to the third Intergeneration Report (Australia to 2050 – Future Challenges) handed down by treasurer Wayne Swan in January 2010, this report identified Australia’s major long-term policy challenges: an ageing and growing population, escalating pressures on the health system, and an environment vulnerable to climate change. Productivity and competitiveness were not the headline acts.

Observation 2: Labor needs to do better with business

Second, the declaration that a Rudd government will seek a new partnership with both business representatives and unions might be best read as both an admission of past failings and a commitment to do things differently in the future. While the intention in brokering a new deal between the major players does not appear to recreate the Prices and Incomes Accord struck by the Hawke-Keating Labor governments during the 1980s and 90s, this new “accord” between unions and business is intended to signal that, this time, Rudd will not deploy the “crash through” approach that characterised many policy reform processes during his first term in office and the Gillard years of minority government.

Observation 3: Labor needs to win

Third, it needs to be kept in mind that none of these issues stand a chance of being developed in any detail unless the Prime Minister wins the next election. Instead, many of the big ticket items included in this new agenda are intended to send conciliatory signals to different audiences that a Rudd Labor Government must win over if it is to retain government.

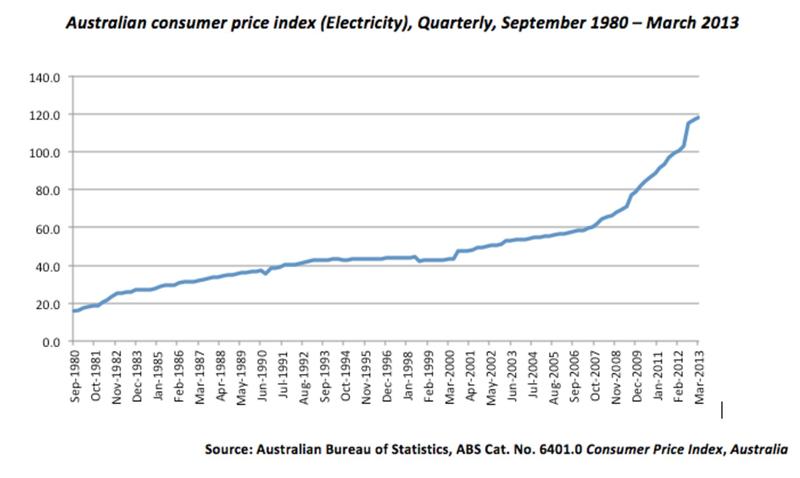

Consider the first big item: electricity pricing reform. This is just one piece in a larger energy policy challenge to business competitiveness and productivity. However, as the figure below shows electricity prices have indeed increased over the last decade at a much faster rate than prior decades. Over the period since 1980, electricity prices have grown by around 640% – a greater part of that increase occurring in the last 15 years. Compared with other major economies in the OECD and the European Union block, this rate of increase in electricity prices now places Australia as having some of the most expensive electricity anywhere. In a booming economy where wages have been growing in real terms, these increases have been less consequential. In a slowing economy, where wage growth has also slowed, this is now a significant issue – not just for productivity, but also for the ordinary punter – especially “working families”.

Addressing “labour market rigidities” is a clear point of political contest between Labor and the Coalition. “Labour market rigidity” is often used as a more civilised way for expressing persistent business concerns about wage and hours regulation, especially minimum wages and overtime regulations. The real agenda for business is obviously to lower wage growth and free up working hours. This is an old problem – as old as industrial regulation itself — and will continue to excite advocates for both regulation and deregulation.

While it is unlikely that a Rudd Labor government will tamper much with the existing industrial relations system, government is clearly keen to signal that is now more business-friendly, and understands its concerns. Here, the point is to signal that a future Rudd government intends to work with business to address new forms of labour market rigidity that limit productivity growth. This was highlighted by Rudd in his emphasis on the importance of “greenfields” sites.

As the economy changes and technological advances disrupt and transform the way we work, traditional forms of regulating occupational health and safety, working hours, employee mobility, and so forth generate new rigidities and constraints on productivity-enhancing innovations. This is particularly true in the case of the growing trend towards teleworking. The challenge here will be to work out ways that regulation can continue to protect employees from labour market risk, while at the same time providing employers with the flexibility to locate new work arrangements that make the most of new technologies.

It has not simply been industrial relations that has soured Labor’s relationship with business. The small business lobby has its own concerns, and the new agenda for productivity seeks to win their support by reducing the burden of inconsistent regulation at state and federal levels, access to capital, and the NBN, among others.

The new agenda for productivity and competitiveness highlights that the burden of productivity improvement does not rest solely on the labour market and with industrial relations reforms. In what may be read as a signal to its traditional support base in the union movement, greater accountability for productivity and competitiveness are to be placed on business itself to lift its game, notably in exploiting new opportunities in Asia.

Observation 4: Labor must restore voter faith

Finally, this speech – intended to be a debate on economic policy with an absent opposition leader – confirms what will become a constant refrain in the lead-up to the election. That the first time round, Rudd had been a fine Prime Minister, capable of steering the Australian economy through the stormy seas of the global financial crisis.

This record, he hopes, will instill a new faith in his future capacity to govern, to manage what will be an even stormier period of economic changes and transition in which we will to face disruptive changes to our economy and established industries. As the mining boom slows, digital technologies continue to destroy “old economy” jobs and upset established ways of doing business, managing transitions to maintain productivity and competitiveness will indeed be the order of the day, whoever is steering the ship. What is not yet clear is whether this new agenda for productivity and competitiveness provides key constituencies with the signs of renewal that this new leader is hoping for.

This article and images first appeared on The Conversation.