The national debate over climate policy hasn't yet canvassed how the ALP or Coalition might approach negotiations on a major new climate treaty in Paris in 2015.

These talks aim to produce a new agreement with all major emitters to come into effect in 2020, and to close the gap between voluntary emissions reduction targets and what's necessary to reduce the risks of warming by more than two degrees Celsius.

There is bipartisan support for Australia’s voluntary target of reducing national emissions by a modest 5% by 2020.

Yet this target falls well short of the minus 25-40% range recommended by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change for developed countries.

What commitments have the parties made?

The Australian government led by Julia Gillard committed itself to a second period under the Kyoto Protocol from 2013 - 2020. While this stance has received informal support from the Coalition, it is unclear whether this would continue.

The centrepiece of the Coalition’s Direct Action Plan focuses on reducing emissions through the sequestration of carbon in soil, which is not recognised by the Kyoto Protocol.

Yet the biggest problem with the Coalition’s plan is that it can provide no assurance that a voluntary scheme based on government carbon buy-back can reach more ambitious targets in the longer term, especially given that the budget for the buy-back is capped.

The plan has a section called ‘International Responses to Climate Change’ but this is merely a survey of what other countries are doing. There is no discussion of the Durban roadmap to Paris in 2015 and the implications for national policy.

What the ALP and Coalition's language tells us

[Labor] repeated the message that Australia was not ‘going it alone’ but behaving as a good international citizen by merely doing our ‘fair share’.

The Gillard government had sought to legitimate its 'Clean Energy Future' package as a nation-building, modernising reform. It therefore focused mainly on what the package could do for Australia rather than what Australia could do for the world. According to Labor, the problem was ‘carbon pollution’ and the solution was the 'Clean Energy Future' package, which would make us ‘cleaner, smarter, richer’ while shielding low income households from the effects of higher energy prices during the transition.

The Gillard government remained engaged with the multilateral negotiations. Under attack from the Opposition, it repeated the message that Australia was not ‘going it alone’ but behaving as a good international citizen by merely doing our ‘fair share’. We were neither out in front nor behind but rather somewhere in the middle of the pack.

In contrast, for the Opposition, the overriding threat to the Australian way of life is not climate change but the carbon tax. Tony Abbott’s climate discourse is laced with terms such as ‘toxic tax’, ‘great big tax on everything’, ‘giant wrecking ball’, ‘a dagger aimed at the heart of manufacturing in this country’. The critique is backed with a ‘blood oath’ to repeal the tax.

The announcement by Kevin Rudd to move from a fixed to a floating price on carbon one year earlier than originally planned has been characterised by the Coalition as merely a carbon tax by another name.

Mr Abbott’s claim that emissions trading is nothing but a ‘so-called market in the non-delivery of an invisible substance to no-one’ takes to new levels the reliance on palpable things .. as .. more authoritative than.. science or economics.

The Opposition’s relentless attack on any price on carbon has meant that very little national attention has been given to national and international consequences of a warming world. Instead, the Opposition has invoked the authority of every day, unmediated common sense and experience rather than abstract climate science, which has been variously denied, denigrated, downplayed or only accepted in muted terms.

Mr Abbott’s claim that emissions trading is nothing but a ‘so-called market in the non-delivery of an invisible substance to no-one’ takes to new levels the reliance on palpable things that we can see and grasp, as a more authoritative form of knowledge than modern science or economics.

Likewise, the legitimation of the Direct Action Plan plays heavily on a reward system. Instead of a punitive tax, we are promised incentives and businesses can choose whether to opt in or out. The discourse seeks to cut through the complexities of taxes and emissions trading schemes through an appeal to folksy wisdom, and simple home truths about human behaviour - we respond better to carrots rather than sticks.

By fixating on the short-term, up-front costs to households and business from a price on carbon, rather than the new economic opportunities of a low-carbon energy transition or the long-term economic and environmental costs of delay, the Opposition has summoned a fearful business community and in-ward looking households.

The deeply fractured climate discourses of the major parties clearly reveal fundamental differences over Australia’s role in the world.

While Labor has defended the idea of good international citizenship, this is not the same as leadership, which entails being a front-runner and galvanising others to take action through the force of example.

What we can expect

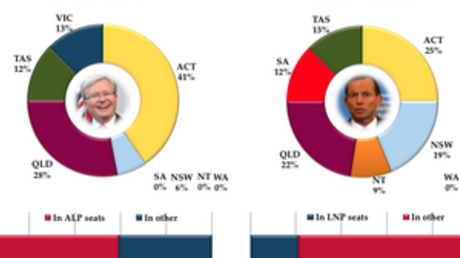

We can expect that a Rudd government would remain engaged with the international negotiations but do little to raise Australia’s mitigation ambition in the near term in the absence of significant action by other parties. Mr Rudd’s new climate discourse is low key, and not designed to galvanise concern for climate change, compared to his bold framing of climate change in 2007 as the greatest moral challenge of our time and a security threat. Any repetition of this earlier framing would have required Mr Rudd to strengthen, not weaken, Labor’s climate policy.

In contrast, the Coalition takes it as given that Australia’s role in the world is to protect its national interests, which includes continuing to enjoy the benefits of a resource rich economy and upholding the (energy-intensive, high consumption) ‘Australian way of life’. Moving ahead of other countries in climate policy is a sucker’s game that will cost us dearly, and send jobs and emissions offshore. The Coalition’s climate-speak naturalises a nation-before-planet discourse through a highly defensive posture towards the world, one in which good international citizenship, let alone activist leadership based on cosmopolitan principles, makes no sense.

We should therefore expect that the Coalition is more likely to play the role of laggard, and possibly even a spoiler, in the international negotiations.